Nicki Minaj and Pretty Taking All Fades: Performing the Erotics of Feminist Solidarity

By Jillian Hernandez and Anya M. Wallace

This essay aims to consider an erotics of feminist solidarity, not a solidarity that only decries the status quo—but one that recognizes the conditions under which women and girls of color craft their identities and sexualities—and does not punish them for it. How do we measure women and girls against a feminism that has not (yet) altered the structures of racism, heterosexism, and capitalism that shape their lives? And have we sufficiently accounted for the joys they experience nonetheless? Drawing on the work of theorists such as Audre Lorde, we define the erotics of feminist solidarity as a forging of alliances grounded in radical sexual politics and attentiveness to the affective and corporeal dimensions of conducting feminist work, even when it is not defined as such.

We engage the explicit sexuality and organic feminism(s) expressed by hip hop artists Nicki Minaj and Pretty Taking All Fades (P.T.A.F.), an emerging performance group of Black teen girls from L.A. who attended Crenshaw High School together. Our arguments are animated by a significant show of feminist erotic solidarity in which Minaj created a freestyle utilizing P.T.A.F.’s viral song “Boss Ass Bitch,” which ultimately landed the group a record deal.[1] We compare Minaj and P.T.A.F.’s work, and its reception, to examine the politics of erotic solidarity in feminist cultural studies.

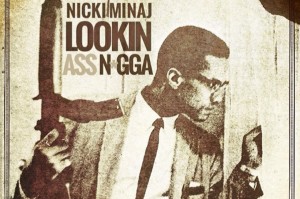

The conspicuous absence of Minaj in recent debates on race and pop culture feminism is troubling. Her current single “Lookin Ass Nigga” (LAN) has not been widely engaged by the feminist blogosphere, yet she has been intensely criticized for her promotional use of an image of Malcolm X. Her appropriation of X, a figure she identifies with in her critique of disciplinary surveillance, was described as tasteless, exploitative, and endangering to youth of color. There have been two blog postings to date by women of color feminists that defend Minaj, but maintain a rejection of her use of X’s image as inappropriate and senseless. Can appropriation as a creative strategy only to be employed in a respectable mode? If so, how has this standard been applied to men’s appropriation of similar historical figures in hip hop? A video circulating online juxtaposes Malcolm X speaking on black self-hate with images of Minaj’s blonde hair, skin complexion, and alleged surgically altered body. She is framed as the antithesis of racial pride, the problem—not white supremacy.

We question the overlooked opportunity for a wide-ranging feminist embrace of Minaj when considering the virulent responses to LAN posted on social media that disparage her:

“Maybe one day she’ll become a real woman and not a retarded teenager”

“WHAT RHYMES WITH NIGGAS? OH I KNOW NIGGAS!….stupid nigga ass bitch…”

“fugazi bitch who she think she talkin to with her fake waffle colored bleached skin plastic weave having fake ass…”

Why haven’t such comments incited a #SolidarityWar?

Similar attacks have been aimed at Pretty Taking All Fades (P.T.A.F.), whose music video “Boss Ass Bitch,” posted in May 2012, has amassed over 12,000,000 hits.  The lyrics of the song are explicit, and demonstrate that the young performers are aware of their sexual selves through language that vigorously describes the pleasure they seek. “If you use your tongue I’ma like that/ Pin my arms to the bed I’ma fight back… Before you eat the pussy you gon’ bite my neck/ Bend me over the bed let me suck it wet.” These vivid directives center on their enjoyment and gratification.

The lyrics of the song are explicit, and demonstrate that the young performers are aware of their sexual selves through language that vigorously describes the pleasure they seek. “If you use your tongue I’ma like that/ Pin my arms to the bed I’ma fight back… Before you eat the pussy you gon’ bite my neck/ Bend me over the bed let me suck it wet.” These vivid directives center on their enjoyment and gratification.

Despite their popularity among peers, P.T.A.F. has been subjected to vicious assaults that continue to accumulate on YouTube;

“These are the type of sluts giving blacks everywhere a bad name.”

“I must be getting behind on my ghetto slang. So ‘boss ass bitch’ must mean ‘ugly ass dirty hoe..’ I’ll try to remember that”

“When the gorilla in the black shirt started rapping, my eyes began to twitch rapidly. Then when I understood what she was saying, I felt my puke crawl up my throat.”

“lol these must be the ugliest ghetto cunts they could find to sing an embarrassing song like this.”

The girls are framed as grotesque and depraved due to their sexually-marked disavowals of respectable heteronormativity. They are deemed unworthy of solidarity.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N6ihCQZK-r0]

P.T.A.F’s raw engagement with sex evokes our roots in marginalized South Florida communities and the young Black girls we encountered there through our work as outreach art educators. Coming from the home of Miami bass booty music where girls and women of color inspire our feminist erotics through spectacular displays of sexuality, we connect to the erotic solidarity forged by P.T.A.F.’s music. We’re reminded of our students at the Miami-Dade County Juvenile Detention Center who craved singing along to the local underground hip hop station while working on art projects in the cellblock. This often sexually explicit music sustained them, and spoke to their erotic and sonic cultures. Denying or critiquing their consumption of this music was never an option. We were there to activate a creative space where they could express themselves through visual art, and in an institution like the detention center, we refused to further police or judge them.

In “Boss Ass Bitch” we find a do-it-yourself, black girl genius—to use Ruth Nicole Brown’s[2] phrase—at work.  The music P.T.A.F. composes is infectious, the video simple, but dynamic in its demonstration of the girls’ commitment to ingenuity. The quality of their production, evidenced by its smooth edits, steady shots, and on-point rhyme delivery—show that this project was not entered into thoughtlessly. Although the song is sexual in content, the girls do not present their bodies as such. Their erotic authority is expressed through their lyricism, while they summon respect as emcees through direct eye contact with the camera. We are compelled by the self-actualization they embody in this vulnerable display of worldwide reach. The video is tangible proof of P.T.A.F.’s bossness.

The music P.T.A.F. composes is infectious, the video simple, but dynamic in its demonstration of the girls’ commitment to ingenuity. The quality of their production, evidenced by its smooth edits, steady shots, and on-point rhyme delivery—show that this project was not entered into thoughtlessly. Although the song is sexual in content, the girls do not present their bodies as such. Their erotic authority is expressed through their lyricism, while they summon respect as emcees through direct eye contact with the camera. We are compelled by the self-actualization they embody in this vulnerable display of worldwide reach. The video is tangible proof of P.T.A.F.’s bossness.

We understand “Boss Ass Bitch” as a learner-constructed educational space informed by the knowledge and desires of the performers—a safe and healthy exploration of sexuality by Black girls.[3] When such spaces are crafted by youth they are often delegitimized in mainstream discourse. Heteronormative regimes dictate that sexual education for youth be rooted in fear and center on the prevention of situations that are not respected (i.e., parenting children out of wedlock, contracting disease, enjoying promiscuity). This framework unduly targets Black women and girls because it is assumed that they are at high risk for unplanned pregnancy and disease transmission more so than their White counterparts; this is underpinned by a chronic urgency to tame a perceived hypersexual nature. Alternative sex education pedagogies focusing on pleasure are scarce among Black women and girls because they conflict with a longstanding assumption that their sexuality must be constrained.

P.T.A.F. and Minaj’s performances of sexual non-conformity trouble this construct and consequently elicit rabid retaliation by the entities they challenge—white supremacy and the patriarchal, heteronormative regimes operative in both the larger culture and communities of color. Minaj’s version of “Boss Ass Bitch,” like P.T.A.F.’s original, engages sexual explicitness and troubles heteronormativity with lyrics like, “Pussy like girls, damn, is my pussy gay? It’s a holiday—play with my pussy day. Pussy this, pussy that, pussy cakin’, pussy ride dick like she a Jamaican.” This queer narration of sexual pleasure and play is a complex expression of female erotics. While cognizant of how the sexualities performed by Minaj and P.T.A.F. may be shaped by male-defined representations of Black female sexuality in hip hop, we do not foreclose the possibility that they experience pleasure in sexual subjectivity.

Yet, while the blogosphere debates the feminism of Beyoncé in the wake of her recent self-titled album, P.T.A.F and Minaj are effectively ignored, relegated to YouTube, and the barrage of negative comments berating them. In an interview, the girls of P.T.A.F admit that these attacks prompted their consideration of abandoning music altogether. Where are their feminist allies?

We do not aim to generate a binary between Beyoncé and P.T.A.F./Minaj here, but question Beyoncé’s swift adoption as the symbol of women of color pleasure politics. We suggest that Beyoncé’s proximity to heteronormativity, secured through the marketing of her married life, affords her this currency. She presents an erotics that is explicit but nonetheless respectable.

What is the cost of respectability in a culture that ignores racism and class disparity? It requires the abandonment of girls and women who perform hypersexuality by ignoring the erotic cultures and identities they stem from. It also denies the organic feminisms they express. Nicki Minaj began making a name for herself in hip hop by performing her music in strip clubs, likely one of the few venues available to her at the time. Minaj doesn’t claim feminism, but does critique male domination and proclaims support for strippers. “Lookin Ass Nigga” has inspired a heightened sense of empowerment among Minaj’s female fans, as did P.T.A.F.’s “Boss Ass Bitch” among our queer students of color.

We argue for broadened possibilities of feminist engagements with pop culture that are reflective of and attentive to the complex erotic connections between cultural producers and their audiences, students and educators, friends, lovers, and families (in their various forms). In many ways this essay is a manifestation of the knowledge that such erotic relations have provided us, both in our personal lives and through our work as educators. When debates over sexual politics more often divide feminists than bring them together, it is crucial to apply our energies toward forging productive and imaginative alliances. Can there be a feminism capacious enough to recognize the potential of erotic solidarity with P.T.A.F., Nicki Minaj, and figures like Beyoncé? We think it’s possible, and are down to rally around them all.

_________________________________________________________

Anya Wallace is a Ph.D. student in Art Education and Women’s Studies at Penn State University, visual artist, and community arts educator. Her research interests center on the intersection of art theory, social justice, literature, and women’s health, and combined with photographic field study documents pedagogies and social activism related to reproductive health, sex, and sexuality among Black women and girls. www.anyamwallace.com @NYNFSuperstar

Anya Wallace is a Ph.D. student in Art Education and Women’s Studies at Penn State University, visual artist, and community arts educator. Her research interests center on the intersection of art theory, social justice, literature, and women’s health, and combined with photographic field study documents pedagogies and social activism related to reproductive health, sex, and sexuality among Black women and girls. www.anyamwallace.com @NYNFSuperstar

Jillian Hernandez, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Ethnic Studies Department and Critical Gender Studies Program at the University of California–San Diego, independent curator, and community arts educator. Her transdisciplinary research investigates processes of racialization, sexualities, embodiment, girlhood, and the politics of cultural production ranging from underground and mainstream hip hop to visual and performance art. [email protected] @lamuchachajill

Jillian Hernandez, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Ethnic Studies Department and Critical Gender Studies Program at the University of California–San Diego, independent curator, and community arts educator. Her transdisciplinary research investigates processes of racialization, sexualities, embodiment, girlhood, and the politics of cultural production ranging from underground and mainstream hip hop to visual and performance art. [email protected] @lamuchachajill

Acknowledgments

We thank Louisa Schein, Ruth Nicole Brown, Mireille Miller-Young, and David Leonard for their insightful feedback on this essay.

[1] Although P.T.A.F. initially questioned Minaj’s use of their song, and stated they were not fans of her work, they did express appreciation for her raising their visibility. When asked about their response in an interview, Minaj did not attack the girls, but defended them as young performers who perhaps were not yet familiar with how the crafting of freestyles in professional hip hop works, were it is common to use someone else’s beat. See http://www.youngmoneyhq.com/2014/02/15/nicki-minaj-talks-to-dj-drama-about-her-boss-ass-bitch-danny-glover-freestyles/

[2] Ruth Nicole Brown. 2013. Hear Our Truths: The Creative Potential of Black Girlhood. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press.

[3] Brent Wilson. (2005). More Lessons from the Superheroes of J.C. Holz: The Visual Culture of Childhood and the Third pedagogical Site. Art Education, The return of visual culture (why not?), 58(6), 18-24; 33-34. National Art Education Association

Pingback: Boss Wisdom from WOTR! Alumni in The Feminist Wire | Women on the Rise! at MOCA, North Miami