“Calling All Stars”: Janelle Monae’s Black Feminist Futures

By Emily J. Lordi

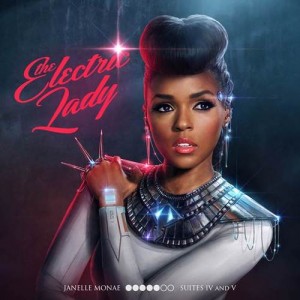

I will let others explain why The Electric Lady, released earlier this month, is Janelle Monae’s most beautiful, expertly pop and unapologetically black album yet. Others will want to decode the lyrics and discuss the newest chapter in the Metropolis saga. I want to talk about the brilliant way Monae has thrown down the Afrofuturist gauntlet. At a moment when the term Afrofuturism can seem like an easy shorthand for all things black and imaginative, Electric Lady makes Afrofuturism less about androids and fantastic other worlds than about the unrealized futures we are living with now. If we are the beneficiaries of past struggle, Monae and the Wondaland artists insist that we are also the inheritors of some long-deferred dreams.

Monae’s album title alone performs a black feminist coup by turning a glorified object into a glorious subject. Here the male fantasy theme park of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland becomes The Electric Lady, a female agent who not only claims a term (“lady”) historically reserved for white women but also seizes the creative power that “electric” connotes. But the title also evokes an era when “electric” became a keyword in American culture—when a nation emerging relieved from the 1970s energy crisis would create the “Electric Slide” and “The Electric Company” and give birth to a neon sneakers-wearing generation of kids with astronaut dreams. Welcome to the future of the past.

The first song presents Monae as the unlikely future of a very masculine musical past. An outsized outlaw’s boast made in the image of Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child” (I am sharper than a razor, eyes made of lasers, bolder than the truth), “Givin’ Em What They Love” chronicles the greatest hits of swaggering tropes, from Peter Tosh’s “stepping razor” to Dylan’s “rolling stone” and Biggie’s Ready to Die. From here, cue a Lenny Kravitz-style open voiced refrain, echoes of Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love,” and the entrance of Prince himself. This fact alone merits pause: when was the last time that Prince was a guest on someone else’s album? But Monae’s re-channeling of gendered power doesn’t stop here. As if less impressed than I am with Prince’s appearance, the album moves right on from Prince to Monae and Badu’s “Q.U.E.E.N.” And with the next track the sonic middle ground surges in like light through the album cover’s neon sign: “Electric Lady.”

This is where things get fun. Solange is the special guest for a party that features go-go percussion, a graciously elastic 1990s R&B dance beat, tight female harmonies a la Destiny’s Child, a great rap by Monae—and Outkast woo-hoos, a random Britney Spears reference, and a vocoded mini-outro just for good measure. Electric lady you’re a star, you got a classic kind of crazy, but you know just who you are… ya’ll make me so proud—the song conspires to make a future of women celebrating other women irresistible.

But this isn’t just about the future. Women have been cheering, admiring and seducing each other in black popular music ever since Bessie Smith’s sexual blues of the 1920s. Nor is Monae’s bending of gender roles new. When Monae reworks the sounds of male artists from Hendrix to Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder and Michael Jackson, the point is not simply that in 2013, women can do everything men can do. It’s also about reanimating a whole history of non-normative pop gender performances. Marvin Gaye’s falsetto helped make the sensitive man—literally brought to his knees with longing for a distant lover—into a potent sex symbol in the 1970s; Prince was posing in the buff on a white winged horse as early as 1979; and Michael Jackson was soon channeling divas like Judy Garland and Diana Ross to create his inimitable androgynous style. The album’s musical allusions remind us how queer American popular music has always been.

Black women are central to this history. I have said that “Givin’ Em What They Love” starts with a male boast, but the first musical figure is a chain-gang grunt that echoes Grace Jones’s Slave to the Rhythm, an album released a month before Monae’s birth in 1985. And we might just as well associate Monae’s gritty vocals on that song with rock icon Betty Davis as with any male star. But the most powerful shadow figure in Monae’s pantheon of pioneering black women might be Lauryn Hill. Monae’s most moving vocals often recall Hill’s contralto sound: the yearning intervals of Hill’s “Ex-Factor” resonate through Monae’s line about her rebel ways in “We Were Like Rock & Roll.” But Monae also uses “To Zion’”s martial drums on the stunning “Victory”; she raps about marching to the streets on “Q.U.E.E.N.” in a cadence that revives Hill’s march through these streets like Soweto; and when on “Sally Ride” Monae sings I know you love me but I’m still gone, she sounds so much like Hill it’s haunting.

For all the genres Monae has mastered, the R&B song of lost love—the ultimate sign of an unrealized future—might be her strongest suit. Witness “We Were Like Rock n’ Roll,” with its bright Smiths guitar line, record-correcting refrain and steady rising gospel choir: No matter how the story’s told, we were like rock n’ roll, we were unbreakable, I want you to know. The album’s long musical memory recalls that “Sally Ride” was a goad before it was a proper name—that the future once sounded like Wilson Pickett’s “Mustang Sally” (“Ride, Sally Ride”), and like Aretha Franklin’s bold sanctifying of that lyric in “Spirit in the Dark,” before it looked like the first woman in space.

With these histories in mind, I keep hearing the album as a field of unrealized futures. I hear the future of black radio, revived in the album’s vexed but bracing skits at station 105.5 WDRD. I hear the alternate future of Hendrix, who would not live to record another album after Electric Ladyland; I hear the lost future of Whitney Houston and the still-possible future of Lauryn Hill. I hear the promise of Michael Jackson, whose presence is so palpable here: in the young striver’s sound of “It’s Code,” the easy beauty of Off the Wall (“Can’t Live Without Your Love”) and the message-y lyrics of “Black or White” (even if it makes others uncomfortable I will love who I am).

Hearing the album as a series of pop afterlives helps explain why Electric Lady ends with “What an Experience,” a song indebted to 1980s synth-pop that references “Red Red Wine.” At the end of this album’s journey, and indeed after Monae has declared I’m packing my space suit, and I’m taking my shit and moving to the moon, the sound of the future is… UB40? This perplexed me until I thought about the dates. Neil Diamond first recorded “Red Red Wine” in 1968; UB40 made it a hit in the mid-1980s. So the song evokes the era of Monae’s birth but also that of her mother’s. You’re the reason I believe in me, Monae sings to her mother in “Ghetto Woman.” The 1968-to-1984 trajectory of “Experience” asks what it means to occupy the space, as Barack Obama writes in his memoir, where your parents’ dreams have been.

Monae’s Afrofuturist art is a humbling and stirring reminder that the future is ours but it wasn’t ours first. Like the TR-808 drum machine, the synthesizer and the spaceship, Monae’s gender-bending performances have sounded like the future for a long time. What can we do to make them sound more like the present? As James Baldwin archly asked when advised to proceed gradually with the black freedom movement, “How much time do you want for your progress?”

These questions are especially resonant at a moment when the March on Washington is commemorated as evidence of a national victory instead of as the first step in a long march toward justice. As the most basic material gains of the civil rights movement are mistaken as the goal of what was meant to be a long-term moral revolution, Electric Lady invites us to reconsider what dreamers of prior eras—those who boycotted buses, went to jail, started breakfast programs and rioted at Stonewall—might have wished for. If we are the future that civil rights activists dreamed of, how much freer were we all supposed to be?

___________

Emily J. Lordi is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She teaches and writes about African American literature and black popular culture. Her first book, Black Resonance: Iconic Women Singers and African American Literature, is due out in October. Her next book will explore the concept of “soul.”

Pingback: mauraweb!» archive » my spaceship leaves at 10

Pingback: Music reviews: “The Way I’m Running” and “The Electric Lady” | Coming to the Edge