The Coiled Spring First Grader Deep Inside: Sexual Violence and Restorative Justice

Content Notice: This article is part of the #LoveWITHAccountability forum on The Feminist Wire. The purpose of this forum and the #LoveWITHAccountability project is to prioritize child sexual abuse, healing, and justice in national dialogues and work on racial justice and gender-based violence. Several of the featured articles in this forum give an in-depth and, at times, graphic examination of rape, molestation, and other forms of sexual harm against diasporic Black children through the experiences and work of survivors and advocates. The articles also offer visions and strategies for how we can humanely move towards co-creating a world without violence. Please take care of yourself while reading.

By Sikivu Hutchinson

Why should we believe her? She’s not a white girl. Hers is not the life story that the media makes visible as gospel, tragedy, and redemption. If she comes forward she could jeopardize her family, its livelihood, its standing in the community. Besides, the real issues that we should be most concerned about are racism, deadly force and the military presence of police in our neighborhoods. Rape and sexual assault are white preoccupations that distract, because, “If you loved your community you would be silent.”

In the toxic litany of messages that black female victims and survivors receive about sexual assault this last is one of the most soul killing, the most deadly. I have written often about how there was no language, program or messaging that existed when I was sexually assaulted as an elementary school student to make my experience visible. I have written less frequently about the shame and disassociation I still feel toward the child who it happened to, the coiled spring first grader nestled deep inside, the one who loved handball, the swings, Electric Company and Golden Legacy comic books.

On the block, in our neighborhood, silence was required for daily survival. Silence meant allegiance to black men and boys splayed in the white man’s radar scope; it meant tacit recognition of their greater suffering, their greater historical sacrifice. Even now, as the political landscape has shifted—as exemplified by the national fury over the lax sentencing of convicted rapist Brock Turner, allegations against Nate Parker and Bill Cosby, as well as Donald Trump’s sexually predatory behavior toward white women—and critiques of campus rape, rape culture and victim-blaming inform mainstream discussions about sexual assault, the specific context of black girls’ experiences are absent from national policy discourse.

The discrediting of black girls’ experiences starts in preschool and kindergarten, where they are taught to endlessly check, police and second guess themselves. It’s symbolized by the hand games that are deemed too aggressive, the dancing that is too “sexual”, the “signifying” that is too loud, disrespectful, and the outfits that the white and Latina girls can wear without getting sent to the dean’s office. It is due in part to this context that—although black women have some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence and sexual assault—we are the least likely to report having been victimized. Even considering the ways in which fear of policing and criminalization in white supremacist capitalist patriarchy hinders us, there is the trauma of constant vilification from within. The Black Church has always played a key role in enforcing this regime of silence. As one of the most devoutly religious communities in the U.S., heterosexist and homophobic attitudes among black folk often perpetuate stigmas against the sexuality of black women and LGBTQ folk. Biblical references to women as property, rape objects, seducers and subordinates who should remain “silent” are still deeply ingrained among folk who attend churches where the public face of leadership and authority is straight, cis and male.

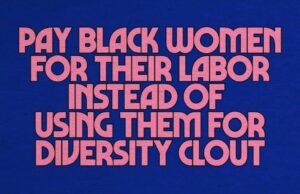

When we do sexual violence prevention work with high school students we begin by talking about the destructive power of misogynoir within the context of their everyday teen lives. It seems as though new terms are coined every month to smear black girls’ sexuality. Over the past few weeks, the term “gerb” has become popular, joining “ho” “thot” “ratchet” and umpteen other epithets designed to check the “hypersexual”, “unfeminine” behavior of black girls. Of course, mainstream vocabulary has always been boundlessly creative when it comes to demonizing women’s sexuality. Walking students through the historical context of these terms (e.g., the way in which “wench” and “Jezebel” were used to justify the rape of black women under slavery by branding them as hypersexual breeders) is critical to providing youth with context about the relationship between racist, misogynist representations of black women in the past and that of the present. Here, rape culture has foundations in the white supremacist imagination which are then reinforced by obstructionist policies around prosecution, law enforcement investigations and inadequate rape kit testing, all of which make it more difficult for sexual assault survivors to come forward.

During a recent Women’s Leadership Project and Young Male Scholars’ peer education training with members of the football team at a South L.A. high school it was clear that the demonization of black girls’ sexuality played a key role in boys’ inability to empathize with sexual assault victims. The explosion of social media platforms has made it easier for young people to participate in sexual harassment and assault through sexually explicit posts that often cause their victims to leave school and/or harm themselves. As the young people talked about the dissing that happens on popular social media sites, virtually everyone in the room admitted to knowing a girl who’d been targeted. According to the Pew Research Center, African American teens access social media at greater rates than do non-black teens. For black girls, online predation—whether it’s through Facebook, Instagram or Snapchat—is also one of the most prevalent sources of sex trafficking. Poverty, joblessness, low access to educational opportunities and high rates of foster care representation all contribute to African American girls having disproportionate rates of domestic sex trafficking victimization.

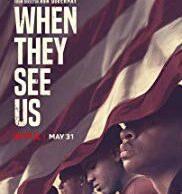

Further, the onslaught of films memorializing and contextualizing victimized white women (be it in portrayals as seemingly disparate as those involving Nicole Brown Simpson, the Manson women killers or Amanda Knox) continues to convey the message that white women’s pain should always have priority. When young people of color see these images ad nauseum they are socialized to believe that they are the most authentic narratives vis-à-vis women’s experiences with abuse and sexual and intimate partner violence.

Restorative justice with accountability means actively engaging and training boys and men to challenge rape culture, sexism and misogyny against black women and girls. It means educating boys and men that when they demean us they are ultimately demeaning their lives, communities and families. It requires a transformative vision of black masculinity, one that confronts the way sexual violence is often framed as a “natural” part of black men’s hetero-normative sense of identity. It demands that community and government resources be shifted to prevention programs as well as therapeutic initiatives that provide critical healing space for victims and survivors—away from the prisons, police, and weaponry that lock down black communities. And it also demands bringing forward marginalized histories of the modern civil rights movement, that with its origins in black women’s resistance to sexual terrorism and rape. Finally, it asks us as black feminists/womanists/survivors who love and work with black children to continue to be on the frontlines as culturally responsive adults bringing the elimination of sexual violence into the narrative of liberation struggle. It is the legacy that our black women ancestors, against the code of violent silence and invisibility in their own homes, families and communities, left for us.

![]() Sikivu Hutchinson, Ph.D., is the founder of the Black feminist humanist high school mentoring program The Women’s Leadership Project and author of the novel White Nights, Black Paradise. She is a contributing editor for The Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @sikivuhutch

Sikivu Hutchinson, Ph.D., is the founder of the Black feminist humanist high school mentoring program The Women’s Leadership Project and author of the novel White Nights, Black Paradise. She is a contributing editor for The Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @sikivuhutch

Pingback: Digging Up the Roots: An Introduction to the #LoveWITHAccountability Forum - The Feminist Wire

Pingback: "It Takes A Village": Afterword to the #LoveWITHAccountability Forum - The Feminist Wire