For June

By Tamara Lea Spira

In our current times of collective struggle’s reinvigoration, the life and works of June Jordan provide vital lessons. Writing between the 1960s and the early 2000s, Jordan’s works archive an arc of social struggle—from the vibrant anti-colonial, feminist, and ethnic power movements of 1960s and 1970s when she came of age; to the brutal intensification of neo-colonialist backlash and the militarization of the globe throughout the 1980s; to US Empire’s near total normalization by her devastating untimely death in 2002.

Throughout this time, June cultivated a poetic praxis that stressed the radical interdependencies of all living beings and entities on this earth. What she so deeply understood—and indeed jointly authored—was a feminist ethic of liberation as collective. In the face of great risk, June was uncompromising in her claim that freedom was indivisible. “The problems of the CIA” and “the problems of the Exxon Corporation” and the problems of the “sneaky creeps in cars,” she enjoined us to see, all resulted in bodily violation and harm, particularly upon Peoples of Color of the world. Justice was not possible for Jordan if any of the violent institutions structuring everyone’s lives were to remain intact. Accepting a politics of anything less than total liberation from all oppressive institutions simply would not do.

The development of June’s theory of total liberation can be traced across the span of her work for nearly half a decade. In her stunning poem eulogizing Dr. King (1968), for example, Jordan indexed the heartbreak of MLK’s murder—a loss that was both excruciatingly particular in its details, and far reaching in its implications for every freedom struggle. As she wrote, the bullets directed at King were intended to issue a death knoll to dignity struggles everywhere: “to kill (and) destroy…(all) freedom growing.”

This razor-sharp politics also applied to her work in 1975 in response to the massacre of protesters in Attica Prison. As Jordan wrote in the “Position Statement on Attica” (1977), the callous murders of those locked up in Attica diagnosed “a racism so profound, so seething,” that no Black person in the US could assume any safety without “militant vigilance” and “perpetual alert.” Moreover, the terror unleashed in Attica empowered the bloodshed of communities struggling for what they deserved across the globe. In her brilliant “Poem Against the State (of Things): 1975,” Jordan attributed the massacre in Attica to:

beasts

unleashed by the Almighty

Multinational

Corporate

Incorporeal

Bank of the World… (228)

These state-sanctioned killers struck communities in multiple nodes of a global counter-revolutionary attack: They were one and the same

[d]espoilers of Harlem

Cambodia

Chile

Detroit

the Philippines

Oakland

Montgomery

Dallas

South Africa

Albany…(228)

Another arena for the development of Jordan’s theories of liberation as total and freedom as indivisible can be found is in her journals and largely unpublished writings in support of revolutions in Latin America. The daughter of Jamaican immigrant parents, Jordan was prescient in the internationalist analysis she forged—an analysis she reminded other feminists was vital decades before “transnational feminism” coalesced as a field in the US academy. In a 1975 essay entitled “Chile: a New Imperative,” Jordan warned those struggling for racial, sexual, economic and gender justice within US borders that the US sponsored Pinochet regime would ricochet far and wide, shaping the contours of oppression and marginalization for all. [1]

Jordan opens the essay with a series of piercing questions. “What does life and death mean to us in America?” she asked. “Can we undertake a moral response to death, to the losers of life and destiny: Can we atone for the lives we take away, the destinies we shunt into extinction?” [2] With these questions, Jordan begged her current and future readers to grapple with the grave inconsistencies of an acceptance with US imperial policy and a commitment to justice in any context. In particular, she highlighted contradictions between the tacit acceptance of CIA sponsored backlash in the Southern Cone of Latin America and a feminist anti-racist politics. For June, the political was personal in the most intimate sense. The marginalized in any locale could not condone the violation of others while remaining intact.

In so doing, she linked complicity with the Dirty Wars with nothing less than a seething corruption of the soul. Furthermore, she asked the hard questions—and not only of those occupying the annals of power and privilege, but also of those marginalized within US borders, through stratifications of race, sexuality, gender, and class: on the fringes of empire.

Book Cover. Living Room, first published by Thunder’s Mouth Press 1985.

Jordan also implied that a failure to protest US backed policies of counterinsurgency signaled complicity with the diminishing value of life for all of earth’s creatures. As militarization, counter-revolution, and privatization deepened in Chile and across the Americas, Jordan saw the writing on the wall for all communities waging struggle for what was theirs. Long before the “the shock doctrine” became a framework for understanding the return of “neoliberalism” to US soil, June was chillingly clear about the implications the disappearance and torture so cruelly exercised on the minds and bodies of Latin Americans. As privatization, gentrification, and the growth of the prison-industrial-complex would come to re-structure the US landscape, Jordan’s early analysis linked emergent modes of social control between disposed communities across national borders.

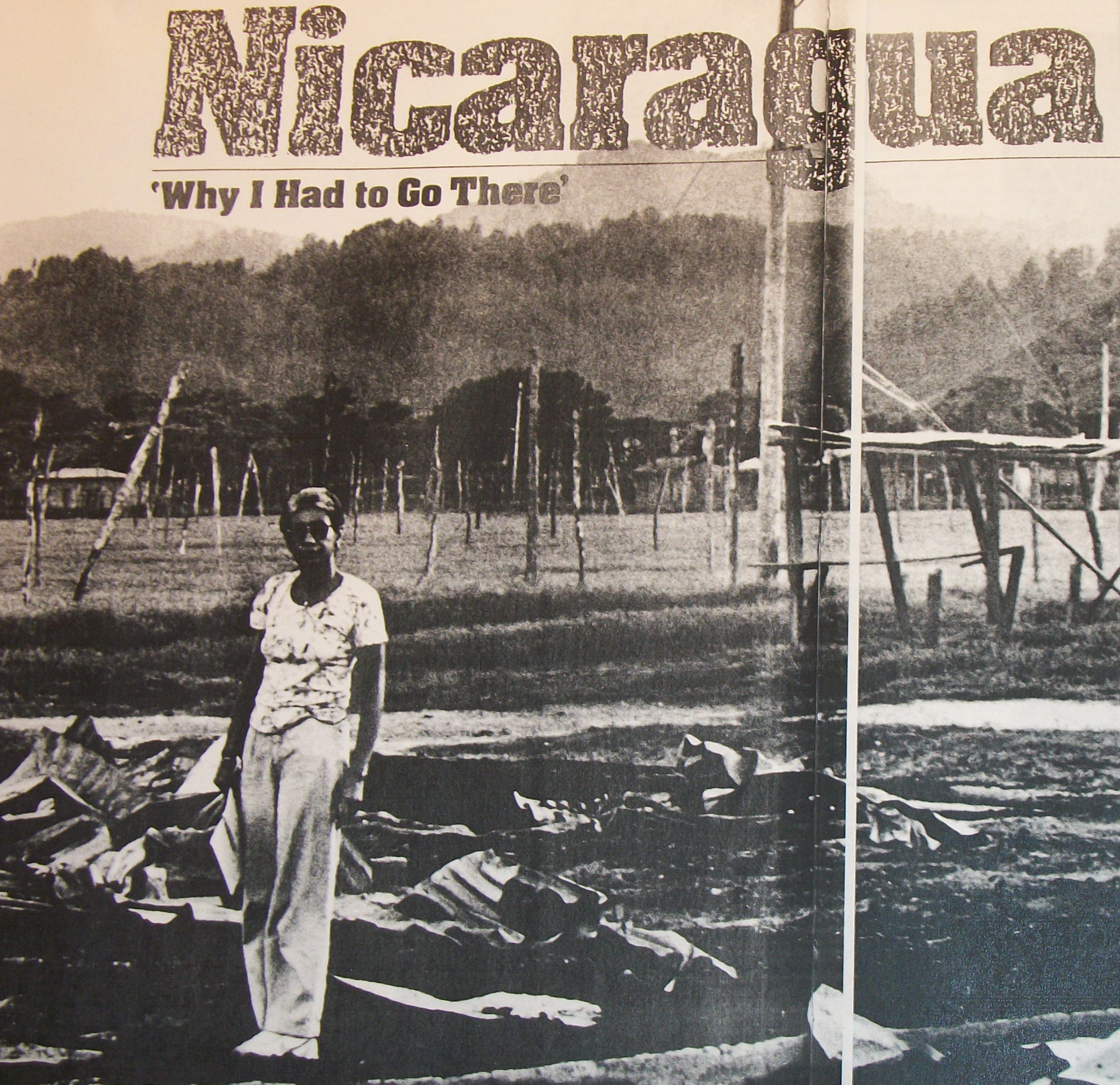

Over the next two decades, Jordan would further hone her ideas about what it meant to be a person marginalized within the US (neo)slave and settler state—especially as US repression of peoples’ revolutions across the world ratcheted up. She was particularly active in resisting the Contra Wars, which were waged in Nicaragua to dismantle the Sandinista Revolution (1979-1990). A relatively late revolution in the arc of hemispheric anti-imperialist struggles, the Sandinista Revolution was unique in its considerations of gender, sexuality, and race. Launched in the early years of Reagan’s inauguration, the Contra Wars were also instrumental in the re-assertion of the US as an imperial super-power, particularly as Reagan’s lethal policies led to the genocide of Indigenous peoples across Central America.

The Sandinista Revolution took place primarily at the hands of very young militants—a fact that Jordan marveled at in the diaries she kept during her travels to Nicaragua (1983). One of the many feminists, queers, and poets who took an active interest in the Sandinista struggle, Jordan was particularly compelled by the actions of Black English-speaking Nicaraguans who lived along the Atlantic coast, and the anti-colonial struggles of Indigenous Miskitu peoples. Jordan struggled earnestly to formulate a solidarity politics that interrogated and accounted for her own privileges, as it also worked to uncover points of what she concluded was an undeniably joint struggle.

In an incredible never-published essay called “Black Power on Nicaragua” (1983), for example, Jordan opened with a conversation she once had with Dora María Téllez. Téllez was the highest ranking and openly out lesbian officer in the FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional or Sandinista National Liberation Front). Upon their first meeting, Téllez remarked to Jordan that the Nicaraguan national hero Sandino and Malcolm X shared a birthday. What’s more, they were were killed on the same day.

Jordan pondered this cosmic connection, using it to propel her theory of “First World Peoples.” For Jordan, “First World Peoples” referred to Indigenous peoples, Black peoples and Peoples of Color across the globe—the majority to whom the fruits of the earth were long overdue. Jordan took Téllez’s words to heart. She urged her comrades back in the United States to recognize their complicity in the slaughter and bloodshed in Nicaragua as accountability toward their mutual liberation.

In a 1983 essay, “Nicaragua: A Lesson in Revolution” Jordan expanded these points, arguing that the growing solidarities between African Americans and Nicaraguans provided a touch-point for a new kind of revolution. Jordan wrote:

I know that the end of the 20th century will finally belong to the majority—First World peoples of the earth who look like me and you—or there will be no one left on the planet. This argument between the rich and the poor is just that serious.

Elsewhere in this same essay, she wrote that:

If other First World people, if we, ourselves, took a notion to think and act to what we felt was good for us, if we thought and if we acted as though the big guys should just take a flying jump out of the nearest window whenever they come pushing their craziness into our countries, our houses, our heads, the whole world would soon become really different really fast: The big guys would lose control and the next thing you know, most of us would find ourselves in the middle of a revolution based on self-respect.

Jordan’s formulation of First World people bespoke the necessary coalitions that would need to be drawn if the entire planet was to survive. Furthermore, she underscored the inevitability of victory if the world’s majorities could band together.

Jordan thus laid the groundwork for a politics of solidarity that would “transform” dispossessed US subjects “from a minority into members of the world’s majority.” Being part of this majority, she concluded, would “mean power” (“Nicaragua: A Lesson in Revolution”). She begged her readers to take to heart a vital lesson: the moment that US white supremacist patriarchal state power etched its deadly incisions on a people’s movement in one corner of the globe, every other freedom struggle was impacted. Based upon this truth, solidarity was the only means toward collective survival.

I leave off with Jordan’s “From Sea to Shining Sea,”which was the opening poem in her brilliant 1985 collection Living Room. Illustrating her reaching analysis, Living Room contains poems on backlash from South Africa to Grenada; from Nicaragua to Lebanon to Palestine to the US under Reagan.

The poem begins with the metaphor of a pomegranate in the grocery store. A symbol of sensuality encased and nature’s commodification, the pomegranate arrives at the store only after a process of violent extraction. It is only available as an object of consumption for the privileged because theft and violence have been waged against all struggling to preserve and protect their lives, labor, and lands.

However, in addition to symbolizing processes of domination, the pomegranate is also juicy and succulent. It is bursting with sensuality and vitality, especially when

split open to the seeds sucked by the tongue and lips

while teeth release the succulent sounds

of its voluptuous disintegration… (325)

It explodes in vibrant, delicious, sensuous color. The pomegranate unifies dispossessed communities once they are reunited to claim that which is undeniably theirs.

It explodes in vibrant, delicious, sensuous color. The pomegranate unifies dispossessed communities once they are reunited to claim that which is undeniably theirs.

I close with the image of the pomegranate as the metaphor for struggles that now burst to rupture our present. June’s words, images, and life lessons prove especially vital today as communities continue in their struggle to claim what is theirs. June’s searing words orient us all toward a politics of solidarity, reminding us all that there is no such thing as sustainability—life or living—outside the framework of collective revolution. Within this context, they serve as generous gifts. I thus write this piece in the form that Jordan so often wrote: as a dedication—For June. Like the sweet purple juice bursting from the pomegranate, her words leave their bold and beautiful trace upon all of those blessed to discover their mark.

___

[1] Jordan, June. “Chile a New Imperative.” American Poetry Review, 13 (November 1975): 39-41.

[2] Ibid.

Tamara Lea Spira is an activist, writer, scholar, and assistant professor who works in the fields of transnational, de-colonial, anti-racist and queer of color feminisms, Hemispheric American Studies, and critical Ethnic Studies at Western Washington University. Spira is currently finishing her first book, Movements of Feeling, which situates the works of Jordan and other feminist poets of her times as interventions into the the amnesias and counter-revolutions of neoliberalism-in-the-making. More on Spira’s current projects and previous publications can be found here: https://wwu.academia.edu/TamaraLeaSpira.

Tamara Lea Spira is an activist, writer, scholar, and assistant professor who works in the fields of transnational, de-colonial, anti-racist and queer of color feminisms, Hemispheric American Studies, and critical Ethnic Studies at Western Washington University. Spira is currently finishing her first book, Movements of Feeling, which situates the works of Jordan and other feminist poets of her times as interventions into the the amnesias and counter-revolutions of neoliberalism-in-the-making. More on Spira’s current projects and previous publications can be found here: https://wwu.academia.edu/TamaraLeaSpira.

She thanks Dana Olwan, Nadia Raza, Heather Turcotte, Keith Feldman, Alison Merz, Anna Agathangelou, Angela Y Davis, and Verónica Vélez for teaching and studying June Jordan’s work with her over the years. Spira dedicates this essay to her incredible students who, in their unequivocal quests for total liberation, so beautifully embody June Jordan’s words:

This is a good time

This is the best time

This is the only time to come togetherFractious

Kicking

Spilling

Burly

Whirling

Raucous

MessyFree

Exploding like the seeds of a natural disorder.

(“From Sea to Shining Sea” 331)

Pingback: "Naming Our Destiny": Afterword to The Feminist Wire's Forum on June Jordan - The Feminist Wire