Deconstructing the Arrest of Sandra Bland

By Erick A. Paulino

By now, most people in the United States know who Sandra Bland is and the circumstances that led to her arrest on July 10, 2105 in Fuller County, Texas. Ms. Bland was pulled over by Texas State Trooper Brian Encinia who alleged she had not signaled a lane change, warranting the stop. In audiotape from their encounter, Ms. Bland claimed Encinia sped up behind her car as she drove, causing her to hastily switch lanes. Three days later, on July 13, Sandra Bland was found dead in her jail cell from an apparent suicide. On July 25, hundreds of mourners attended a funeral service at the suburban Chicago church Ms. Bland had attended.

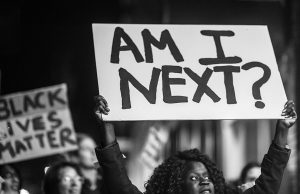

The encounter between Sandra Bland and Trooper Encinia is instructive to motorists of color in many ways. The confrontation also raises a number of constitutional problems regarding citizens’ rights and the seemingly limitless power of police and their unfair conduct. The situation also raises issues that highlight the connection between race and gender and why the movement for #BlackLivesMatter must continue to expand to defend the lives of women of color in the vein of activist campaigns like #SayHerName. While Ms. Bland’s arrest is the latest prominent example of police brutality against people of color, it remains one of the few prominent cases involving a woman.

Video and audiotape from the encounter show that while Ms. Bland was being arrested, Encinia stated he had intended to let her go with a warning. However, after processing documents and returning to her car, the trooper failed to give Ms. Bland the supposed warning. Instead, he interrogated Ms. Bland about her “attitude” and requested she extinguish her cigarette. In doing so, Encinia escalated the situation and intentionally failed to end an encounter that should have otherwise ended without Ms. Bland arrested, criminally charged, and tragically dead.

However, Encinia’s question about Ms. Bland’s “attitude” and his order that she extinguish her cigarette were not designed to investigate. Instead, they were uttered to instigate and to escalate the situation. These were intentional actions to agitate and provoke Ms. Bland—to fire her up in order to arrest her. Encinia was motivated to apprehend Ms. Bland by the rage he seemingly felt when she protested and demanded he explain his actions—when she asserted what she believed were her rights. While not illegal, Ms. Bland’s language and temperament defied a man whose uniform and weapons, male sex, and white race required her full submission. Her defiance insulted and wounded Encinia’s pride—as a cop, a man, and a white person. As a result, Ms. Bland was punished.

But in order to arrest Ms. Bland, Encinia needed a reason. His provocations were attempts to find that reason. They were also informed by racist stereotypes about the “disobedient nature” of people of color and sexist tropes about Black women and their supposedly “ferocious attitudes.” Ms. Bland’s vernacular and temperament did not adhere to the politics of respectability attached to notions of the “model citizen” and “ideal woman.” (Yet, never in the history of the U.S. have notions of honorable citizenry and righteous womanhood been bestowed on Black women, who are considered always already “deviant” and “aberrant”—this was true on the slave ship and on the plantation as it is true today in universities, government offices, and the eyes of the law.) The critical issue here is with how Trooper Encinia problematically perceived Ms. Bland’s actions and speech as “combative.” Furthermore, the node of critique is also how sexist and racist tropes about Black women worked to inform Encinia’s strategy to guarantee punishment.

Had Encinia simply given Ms. Bland back her license with the supposed warning, the “investigatory stop” would have concluded and Ms. Bland would have been constitutionally free to leave. This is because courts have concluded that the moment people are handed back their license and a ticket or warning and are told “drive safely,” the encounter has de-escalated from an investigatory stop to a consensual encounter. Indeed, the U.S. Supreme Court determined in Florida v. Royer that warrants are required for searches and seizures, and that while officers may initiate investigatory and consensual encounters, individuals are at all times free to leave in the latter situation. The majority decided in the 1983 case that: “The person approached, however, need not answer any question put to him [or her]; indeed, he [or she] may decline to listen to the questions at all and may go on his [or her] way.” Since people are free to leave a police encounter if they are neither detained nor arrested, they should persist to ask if they are being detained or are free to go.

Accordingly, had Ms. Bland asked if she was free to leave when Encinia walked back to her car, he would have, at least, been legally compelled to let her leave with a warning. Likewise, Ms. Bland could have refused to entertain the officer’s question about her “attitude” had she exercised her Fifth Amendment right to silence. However, naïve of their rights and intimidated by officers’ presence and demeanor, most people rarely feel comfortable voluntarily leaving encounters with police officers.

In fact, the moment Encinia returned back to Ms. Bland’s vehicle is an obvious example of the coercive nature of traffic stops. If Ms. Bland haphazardly switched lanes because Encinia sped up behind her, surely he ensnared her into committing the alleged infraction. This and similar types of illegalities are routinely committed by law enforcement against people of color and are incentivized by bureaucratic polices binding monies to traffic citations and federal grants to data showing rates of charges and arrests (i.e., the prison industrial complex). Thus, many times even when people are handed back their documents and citation or warning, the officer will probe further and ask some new investigative question. (Granted, sometimes further questioning occurs for legitimate reasons, like asking if the person had anything to drink or is carrying any weapons.) Alas, under pressure and not knowing their rights, people will continue dialoguing and sometimes even consent “voluntarily” to searches of their bodies and vehicles.

Rightfully indignant with Encinia’s provocations, Ms. Bland became increasingly upset, especially after he ordered her to extinguish her cigarette. She probably felt something not unfamiliar to people of color overwhelmed with indignation in the face of racist violence. Despite how she expressed herself, Ms. Bland had every right to question Encinia’s request that she extinguish her cigarette while she was in her own vehicle. She knew it was not a reasonable request for the trooper to make. In fact, the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted her the right to keep smoking. While Encinia could technically have argued that the cigarette and its smoke was interfering with “legitimate police business,” this is unlikely since he had already processed papers—was about to give her the supposed warning—when he ordered Ms. Bland to extinguish her cigarette.

When Ms. Bland refused to extinguish her cigarette, Encinia ordered her to exit the vehicle. The “exit order” came because he used her “combative attitude” (which he provoked) to articulate a concern for his “personal safety,” which is the main reason police officers issue “exit orders” in traffic stops. When Ms. Bland verbalized her rightful frustration with what Encinia repeatedly vociferated was a “lawful order,” the officer interpreted her protests as a refusal to comply with the order, which was indeed a technical violation that compelled him to initiate arrest of Sandra Bland.

Then, when Ms. Bland continued to verbalize her discontent with the arrest order, Encinia pursued the arrest with an “enhanced” count of “resisting” arrest. This is because according to Texas law, a person can “resist arrest” in a number of ways that do not necessarily require physical contact with a police officer. Anything used to avoid detention—like being “combative”—is considered resistance to arrest. (Interestingly, if a person is prosecuted for resisting arrest in Texas, he/she cannot use as a defense the fact that the arrest was illegal.)

In the end, Encinia’s strategy worked. He misused his authority to emotionally manipulate Ms. Bland into his premeditated entrapment. His provocations are racist and sexist iterations of what can be called a “soft” form of police brutality. This, of course, was followed closely by the use of brute force as Encinia threatened to “light” Ms. Bland with his Taser then threw his upper body over hers to forcibly eject her from her vehicle and violently apprehend her. At play here are gendered and racialized politics of affect and the body.

Indeed, Encinia knew his uniform, gun, and whiteness granted him power over Ms. Bland. And he was also aware of his gender privilege and masculinity—a benefit he unleashed when he physically projected his body over Ms. Band to forcefully eject her from her vehicle and subsequently arrest her.

Thus, in challenging racial profiling and police brutality against people of color, #BlackLivesMatter activism must pay particular attention to how police exercise force differently for men and women, as well as for LGBT+ people, especially transgender individuals and others whom are variously gender non-conforming.

Despite what some erroneously believe, it is perfectly rational to question the demands of a police officer, especially when they seem unlawful. Indeed, police officers are not “the law.” They are public servants paid by taxpayer dollars to enforce laws and maintain public safety. Like all public servants, they need to be responsive to the critiques of a public dissatisfied with their delivery of a service that same public pays them to do.

Sandra Bland adamantly voiced her dissatisfaction with Encinia’s execution of his job. As a result, she ended up violently arrested and sent to jail where she tragically died. Given the disadvantage people of color have in traffic stops, legal experts suggest they should “comply now, contest later.” Yet, if balking at police is always a bad strategy, it appears pandering to them seems to do little for people of color, especially in a criminal justice system where innocence until proven otherwise is not a dictum uniformly applied to people of color.

Our current historical moment unfolds itself as a critical juncture for the continued struggle of Black liberatory politics. One of the powerful consequences of movements like #BlackLivesMatter is its fervent deployment of African diasporic discourses of resistant thought (epistemology), action (praxis/kinesthetic) and feeling/temperament/expression (affect). This is true even as those same vernacular traditions are continually maligned and re-appropriated (without attribution).

However, the Sandra Bland case demonstrates that in many ways, the best option for people of color dealing with an abusive police officer is to try as much as possible to tactfully control the situation. Sometimes that means remaining as silent possible, without ever consenting to bodily or vehicular searches, never resisting arrest, and continually asking if one is being detained or is free to leave the encounter. Subversive resistance (as performance studies scholars have told us) is a politics of many forms—including tactful silence.*

*For more on resistance and performance, see: Muñoz, J.E. (1999). Disidentifications: Queers of Color And The Performance Of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Also consult: Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ wa. (1988). Enactments of Power: The Politics of Performance Space. TDR, 41(3): 11-30. See also: Raby, R. (2005). What is Resistance? Journal of Youth Studies, 8(2): 151-171.

_________________________________

Erick A. Paulino is a Ph.D. student in gender, sexuality and feminist studies at Arizona State University. He holds a B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. He was born in Santo Domingo (Dom. Rep.) and lives in Miami, FL, where he works in community organizing and HIV prevention. He spends a lot of time thinking and writing about the intersections between gender, race and sexuality.

Erick A. Paulino is a Ph.D. student in gender, sexuality and feminist studies at Arizona State University. He holds a B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. He was born in Santo Domingo (Dom. Rep.) and lives in Miami, FL, where he works in community organizing and HIV prevention. He spends a lot of time thinking and writing about the intersections between gender, race and sexuality.

2 Comments