Profiting from Rape: Sexual Violence and the Capitalist State

By Kelly Rose Pflug-Back

Rape culture. Although a somewhat new term, it unveils a truth which countless women and girls have known on both an intellectual and a visceral level since the advent of patriarchy: that sexualized violence and the objectification of female bodies underpins the fabric of mainstream society. Rape, when it comes down to it, is normal. Society often feels neutral towards its perpetrators (provided that they are white, and preferably wealthy), while its survivors are scandalized, ridiculed, or silenced. Rape culture is the social climate which allowed Rehtaeh Parsons to be violated and brutally mocked by her peers, and the legal norms which allowed those who remorselessly harmed her to walk off scott free. It is the fact that marital rape was legal in Canada until 1983. It is the fact that “Pick up Artist” tutorials have built a booming industry around advising men on strategies for sexual harassment, and the reality of“revenge porn” sites continuing to flourish despite the profusion of freely available pornography made by consenting individuals.

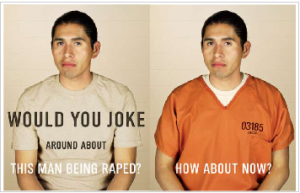

The naming of rape culture is a powerful act, but its theoretical and political potential is in danger. We tend to see rape culture as something which effects women and girls we can relate to, in environments which we recognize: in bedrooms, college frat houses, workplaces, on the street at every hour of the day and night. We tend to believe that we, as feminists, are not complicit in it, while failing to see that it is an integral component of the economic and political systems which we take for granted as normal and unavoidable. Women working in sweatshops, mines, and other sites of neo-liberal capitalist exploitation suffer egregious acts of sexual violence on a daily basis, yet we fail to name capitalism as an aspect of rape culture. Thousands of women, men, and minors suffer debilitating, sometimes fatal sexual violence as part of civil conflicts worldwide, yet we fail to name the political and economic agendas of powerful states and corporations which support or exacerbate these conflicts as an aspect of rape culture. Countless men and women are raped in prisons and immigration detention facilities, yet we refuse to name borders or the carceral system as an embodiment of rape culture; on the contrary, many feminists support the idea that incarceration and increased policing are a solution to sexual violence.

Since the most recent evidence of U.S.’s involvement in torture surfaced last December, mainstream feminism has generally remained revealingly silent on the issue, despite the fact that many of the atrocities which took place involved rape and sexual assault. Among the abuses against prisoners in Guantanamo and other secretive CIA prisons outlined in the 525 page Senate Torture Report, we hear of men being anally raped under the guise of unnecessary medical procedures known as “rectal feeding” and “rectal rehydration.” We hear of a female prisoner wishing to end her own life after watching guards rape her adolescent son. None of this should have been surprising to the public. These words and images have been a part of the Western public psyche since Abu Ghraib; and before that, their precursors reach back much farther. Lynchings, slavery, medical experimentation, colonial genocide–a history of racialized and sexualized dehumanization and Othering which is as old as our colonial countries themselves and inextricable from their birth as modern nation states. Our history is a dimly lit wax museum filled with scenes as horrifying as anything depicted in the slasher films our culture so greedily consumes.

When we talk about reasons for opposing the rise of “surveillance society,” we usually do so from a civil liberties perspective. Yet these encroachments into our private lives carry an undeniable peeping-tom aspect. Police in the U.S. have used their search powers to create a “game” in which they swapped explicit photos stolen from the phones of arrested women, and numerous police infiltrators in the U.K. have had sexual relationships and even fathered children with female environmental activists who they were being paid to spy on. While these behaviors could be brushed off as a poor choice, lack of self control, or compromised ethics on the part of informants, Gary T. Marx, professor emeritus of sociology at M.I.T., has documented the use of sex as a tool used by infiltrators for the purpose of building false trust.

When perpetrators are heterosexual men and their victims male, it becomes less easy to pin rape culture as a whole upon the narrative of men and boys deriving sexual satisfaction at the expense of another, less powerful person’s bodily autonomy. Rape culture is not only systemic, but also systematic; it is not simply a symptom of pathologically selfish sexuality, but also a system through which those with more power assert which bodies are sub-human, which bodies can be tortured, incarcerated, and killed with impunity in order to serve the economic and political agendas of powerful states.

For decades, feminist movements have been fighting to educate society that rape is first and foremost about power. Not sex, not morality, not women’s actions or styles of dress, but the violent assertion of power and dominance. What we need to start acknowledging in order to move forward in terms of meaningful solidarity between social movements is that power, or rather the asymmetrical construction of it, is also about rape. We speak of rape culture as though it is something separate from the neo-liberal state, as though the state can save us from it through punishing and incarcerating dangerous men (an alleged solution which, in terms of the number of rapists being charged let alone convicted, is far from being realized). This narrow viewpoint, however, paints over the fact that the state and the prison system themselves are not only perpetrators of rape culture; they are master architects of it.

Without demonstrated, tangible solidarity among oppressed groups, the work which we do in the world as feminists will be limited in its scope and ultimately in its transformative power. Today, certain classes of women have in many ways been freed from occupying the patriarchal role of sexual and domestic servitude which they were once compressed into. Yet as long as we live within the fetters of unequal power structures, someone’s body must bear that abjection. Wealthy white women shatter glass ceilings in the corporate workplace, while the domestic labour which was once demanded from them is increasingly performed by underpaid migrant women who are systematically denied even the most basic rights. Canada and the United States sing the praises of gender equality in their allegedly civilized liberal democracies, while brutal rape and murder of countless Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people within their borders continues to be both sanctioned and perpetrated by state powers. Without criticism of neo-liberalism, feminism becomes yet another tool for inclusion and accommodation within a power structure which is inherently unequal. In a hierarchical system, there is not enough space for everyone at the top -or even in the middle- and the assertion and maintenance of this inequality will continue to be done not only through hegemony and coercion, but also through the violent objectification of those whose oppression is necessary for the survival of the capitalist state.

Kelly Rose Pflug-Back is an award-winning writer, student, and social activist based in Toronto. Her poetry, articles, and short fiction have appeared in places like the Toronto Star, the Huffington Post, Counterpunch, Write, and This Magazine. She recently finished a BA in Human Rights and Human Diversity from Wilfrid Laurier University, and her first book of poems, These Burning Streets, is available from Combustion Books (2012). Follow her on twitter at @kellypflug

Kelly Rose Pflug-Back is an award-winning writer, student, and social activist based in Toronto. Her poetry, articles, and short fiction have appeared in places like the Toronto Star, the Huffington Post, Counterpunch, Write, and This Magazine. She recently finished a BA in Human Rights and Human Diversity from Wilfrid Laurier University, and her first book of poems, These Burning Streets, is available from Combustion Books (2012). Follow her on twitter at @kellypflug

Pingback: Profiting from Rape: Sexual Violence and the Capitalist State | Kelly Rose Pflug-Back

Pingback: Sunday feminist roundup (12th April 2015) (feimineach)

Pingback: OUR SUNDAY LINKS | GUTS Canadian Feminist Magazine

Pingback: Consent, Compromise, and Libidinal Drives | Speculative Fiction