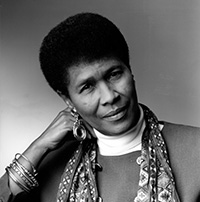

Personal is Political: Toni Cade Bambara of Simpson Avenue

By Guest Contributor on November 21, 2014By Nikky Finney

I was 21 and graduating from college in one week, headed to graduate school. Dr. Gloria Wade-Gayles, my professor and mentor, had carefully written down Toni Cade’s address and phone number on an index card, in longhand, like a recipe out of some family cookbook. “When you get to Atlanta find Toni Cade. She’s expecting you. ”

I knew this tradition. Older Black women handing over younger Black women to the next Black woman in line for her Finishing work. It took me several weeks to get up the nerve to call. Next thing I knew, I was walking up the hill to Toni Cade’s Pamoja writing workshop. This was the only writing workshop I ever attended in my life. We were students and nurses and bus drivers, anyone who wanted to know more about writing and storytelling.

Early one morning, on the very day one of our workshops had gone on from 12 noon to 8 p.m., Toni Cade called and woke me up. It was 2 a.m.

Nikky, I need you to come and pick me up.

Fifteen minutes later, with a loose jacket falling over my pajamas, I drove through a bright starlit sky to Simpson Avenue. I pulled into her driveway. She put out her cigarette out and got into the passenger seat.

_________ is in trouble. She moved in two weeks ago with that new brother…the one with the big smile…works at the Co-op…he hit her when she first moved in, and he’s still hitting her…we’re going to get her…told her to put everything she could carry in some pillowcases and be at the door…he’s not home now…we only have a little time.

_________ was a member of Pamoja, and I had noticed she had not been herself of late. She was an utterly brilliant young writer. ________ was a sweet tender-hearted woman, too. She hadn’t been to Pamoja in a while, and I had been too polite to inquire about where she might have been.

We pulled up, and _________ was outside standing in the near dark with her arms folded around herself. At her feet were four stuffed pillowcases. Everything __________ owned in the world was in them. Our eyes found each other through the windshield, in the headlights and half-darkness. I put the car in park, but didn’t cut the engine. I got out, looking around. Nothing felt safe. We worked quickly. Nobody was talking. Toni Cade got out of the car, and took two stuffed pillowcases and put them in the trunk of my Volkswagon. I took the other two and put them in the back seat. _________ got in and closed the door quietly. I drove Toni Cade and _________ back to Simpson Avenue, and helped them get everything inside.

What if he comes here looking for her?

I whispered.

He won’t.

is all Toni Cade said.

I gave ___________ a hug. She eased down into the same chair that earlier in the day Toni had sat in during workshop talking to us about community and the power of Black folks. I could hear __________ start to cry as Toni closed and locked the door.

For two years, I had walked up the hill to Toni Cade’s house hoping to learn how to become a writer. I had listened to every powerful word she ever uttered as she nurtured and guided us in the art of truth-telling and the Black storytelling tradition. But that night, as I stood on Simpson Avenue unable to go home just yet, the definition of who and what a writer must be came crashing down through the stars.

Nikky Finney was born in South Carolina, within listening distance of the sea. A child of activists, she came of age during the civil rights and Black Arts Movements. At Talladega College, nurtured by Hale Woodruff’s Amistad murals, Finney began to understand the powerful synergy between art and history. Finney has authored four books of poetry: Head Off & Split (2011), The World Is Round (2003), Rice (1995), and On Wings Made of Gauze (1985). The John H. Bennett, Jr. Chair in Southern Letters and Literature at the University of South Carolina, Finney also authored Heartwood (1997), edited The Ringing Ear: Black Poets Lean South (2007), and co-founded the Affrilachian Poets. Finney’s fourth book of poetry, Head Off & Split was awarded the 2011 National Book Award for poetry.

You may also like...

2 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Liberation Legacy: Fifteen Years of the Toni Cade Bambara Scholar-Activism Program and Conferences at Spelman College, 2000-2015 - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire