I first met Toni Cade Bambara at a poetry reading. We were at the Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC), an elementary school turned center for black arts in Atlanta. It was 1977, and Toni was Writer-in-Residence, along with Atlanta poet and social activist Ebon Dooley.

That initial meeting was followed by random sightings of Toni at Freedom Food Coop or at the Shrine in West End, but most often in the hallways of the NAC, where my husband Jikki and I hung out while the children attended class. I knew her name but not her work. I decided to read her short story collections Gorilla, My Love and The Sea Birds are Still Alive. Toni was a natural storyteller. She wrote about the diverse ways we are Black, about issues of identity often told through the lives of women. She wrote like she communicated; like it was just you two in a room, and the conversation was really a story unfolding.

That initial meeting was followed by random sightings of Toni at Freedom Food Coop or at the Shrine in West End, but most often in the hallways of the NAC, where my husband Jikki and I hung out while the children attended class. I knew her name but not her work. I decided to read her short story collections Gorilla, My Love and The Sea Birds are Still Alive. Toni was a natural storyteller. She wrote about the diverse ways we are Black, about issues of identity often told through the lives of women. She wrote like she communicated; like it was just you two in a room, and the conversation was really a story unfolding.

I got to know Toni during weekly meetings she and Ebon facilitated to discuss creation of a Black writers’ collective in the South. I remember sitting in a classroom filled with writers, some who also identified as dancers or mystics, painters, and musicians. These meetings were not like any meetings I attended in the past. Toni chose her words carefully, gently nudging us toward revolutionary action as we discussed the role and responsibility of the writer as member of a community and a movement.

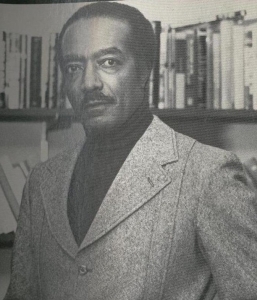

Toni opened her address book and her home to us. Broke bread with us and allowed us to share her friends. She introduced us to a pantheon of Black writers, editors, publishers and presenters. One of the first people she introduced us to was Hoyt W. Fuller, a leading conceptualist of a Black literary esthetic. Hoyt was managing editor of Black World, a monthly literary journal. When Black World ceased publication in 1976, Hoyt founded and edited First World.

The meetings continued throughout the summer, and I soon discovered that Toni was a master of the art of the question. I don’t remember her ever making a decision or telling us what to do. I do remember hour after hour of discussion where anything could be and was said, as we debated the name and purpose for our writers’ organization.

Looking back, I see Toni’s first question was about the name for our proposed organization. Some of us thought that was backwards—why discuss a name before you know what you are organizing? But Toni kept asking the question of name. Week after week, we threw out words and phrases, and then examined their implication from every angle. With each discussion, we began to develop an understanding—that we could not speak of the organization or our work without considering at every turn how our words linked us back to our community. Out of those discussions came the name Southern Collective of African American Writers. Our mission was to work in and with our community and to use the written word to liberate us and our community.

That clarity, along with Toni and Ebon’s leadership, allowed us to make a commitment to organizing a conference to build the organization. At the time, I was earning my keep as freelance reporter for the Atlanta Voice newspaper, working with another mentor: J. Lowell Ware. An offset printer, I also ran the small quantity print jobs on the offset press.

I could make the time to volunteer, so I began to take on some responsibilities for the Southern Collective of African American Writers. The work evolved. But the hands-on-deck for day-to-day work dwindled. Ebon and Toni asked me to take on the unpaid job as coordinator for a nine- state regional conference. Soon, I was logging 40-50 hours a week toward our goal.

This began a planning process of late night telephone conversations between Toni and me. After we discussed progress with the conference, she would pull out her address book, and I would gather my own list of community resources and volunteers. After identifying what we needed to move forward, we would each throw out names and ask the questions—who can do what to help us move forward? What is the best approach to get what we need?

Toni taught me never to ask people for something they clearly cannot deliver. Even if they commit, because we asked for more than they realistically could deliver, they will feel guilt. If this happens, she warned, we lose them as part of the work and maybe as a friend.

We never spent time discussing anything negative. Toni taught me to jump-start my thinking by beginning from a place of love. Believe that what we want to accomplish is in the better interest of the community and, through careful planning, the community will give us what we need. Years later, I realized this was Toni’s way of teaching me community organizing as strategic thinking grounded in love. She anchored me in the belief that everyone wants to do something to help the community, and my job was to find that one thing and then ask for it.

Toni and I worked together for three years planning the annual SCAAW conference. Every once in a while, she’d end our call with a question. Her question was always simple and direct, always about my personal growth.

She once asked me, “Alice, what do you want from life?” I rattled on about the world I wanted my children to inherit, my goals for their future, what I would like to see for Jikki. Toni let me talk, and when I was done, she spoke. “I didn’t ask what you want for others, Alice. What do you want for yourself?” Then, she hung up.

That question made me lose a lot of sleep. On future calls, Toni never asked me for an answer. It took me three weeks to answer her question. Three weeks to break down the learned behavior and thinking that separated me from my heart’s desire. Three weeks to deconstruct the social and cultural norms of the 1950s that demanded I always be the dutiful daughter, the obedient wife. So at the end of a call when Toni began her goodbyes, I confessed. “I want to write, Toni. I want to be a writer.”

Then, she did it again. “What is keeping you from being a writer?” Even though I had been writing news stories, stage plays, and poetry for years, I started to babble about reviewers and critiques about publishers and editors. Then she asked, “Are you telling me someone has to say you are a writer before you can be a writer?” She hung up, and again I was left to unpack all those toxic ideas waiting to defeat me, buried in my heart and my thinking.

Her questions gently guided me to claim my life as a writer. Through the years, Toni asked me many questions that lead to me owning my gifts. Her questions led me to the realization that I was a natural teacher. Her questions forced me to value my writing and to request payment for my performances. She guided me to a place where I could claim my job as a cultural worker. Her questions lead me to create a life doing what I love, and earning my way in the world.

I believe Toni saw me as a living laboratory for the teaching and nurturing of a cultural worker grounded in revolutionary love.

I am deeply grateful for Toni’s gifts, and strive to multiply them in my life.

Alice Lovelace is a cultural worker, poet, playwright, teacher and performer. She is co-editor of “Art Changes” at In Motion Magazine, an on-line journal dedicated to issues of democracy. Alice earned her Master’s in Conflict Resolution at Antioch University’s McGregor School. Her focus is on community art as a form of mediation. In 2011, Alice and visual artist Lisa Tuttle collaborated on “Harriet Rising,” commissioned by the City of Atlanta Office of Cultural Affairs Public Art Program and Underground Atlanta, for its four-month long Elevate: Art Above Underground exhibit. The installation remained for a year at Underground Atlanta, and was named one of the 50 best public art projects in the nation by Americans for the Arts’ 2012 Public Art Network Year in Review. Alice is a veteran organizer, and considers her most rewarding effort to be as National Lead Staff Organizers for the first United States Social Forum, a five day gathering in June of 2007 in Atlanta, GA. The Social Forum was attended by 15,000 organizers and activist from the United States and around the world. For more information, please visit: http://www.alicelovelace.com.

Alice Lovelace is a cultural worker, poet, playwright, teacher and performer. She is co-editor of “Art Changes” at In Motion Magazine, an on-line journal dedicated to issues of democracy. Alice earned her Master’s in Conflict Resolution at Antioch University’s McGregor School. Her focus is on community art as a form of mediation. In 2011, Alice and visual artist Lisa Tuttle collaborated on “Harriet Rising,” commissioned by the City of Atlanta Office of Cultural Affairs Public Art Program and Underground Atlanta, for its four-month long Elevate: Art Above Underground exhibit. The installation remained for a year at Underground Atlanta, and was named one of the 50 best public art projects in the nation by Americans for the Arts’ 2012 Public Art Network Year in Review. Alice is a veteran organizer, and considers her most rewarding effort to be as National Lead Staff Organizers for the first United States Social Forum, a five day gathering in June of 2007 in Atlanta, GA. The Social Forum was attended by 15,000 organizers and activist from the United States and around the world. For more information, please visit: http://www.alicelovelace.com.

You may also like...

4 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Praise to the Writer - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: For Toni and the Sisterhood, with Love... - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Liberation Legacy: Fifteen Years of the Toni Cade Bambara Scholar-Activism Program and Conferences at Spelman College, 2000-2015 - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire