F-Bombs to Live By: Feminism, Faith and Functional practices

By Stephany Rose

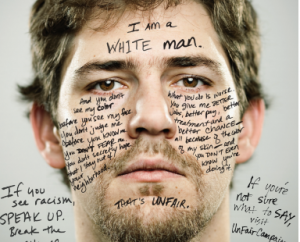

Though having to directly assert such a position is evidence for why my work of Abolishing White Masculinity is so critical in this present day race conversation.

When I tell people I’m a professor, they are initially congratulatory and delighted. When they ask what I teach, many are become confused; “women and ethics,” they ask. “No, women’s and e-th-nic studies,” I repeat. When I tell them that I am a critical whiteness scholar and consultant who specializes in white masculinity, they are stunned, bewildered even, and left without knowing how to continue the dialogue. Reading my body—a still relatively young, black woman—many people in direct conversation do not know how to receive my intellectual interests, whether in academic or non-academic space.

Of course, race/ethnic and gender studies are not new phenomena. However, the direct study of white men, in academic field years, is a relatively new space of intellectual engagement for a number of reasons. The most prevalent and direct reason being the presumed assumption that dead white men were always already being studied by default under the liberal arts umbrella. There is culturally historical merit to this line of thinking, but academically it fails by ideologically positing white men as ubiquitous human beings unworthy of being called out and examined specifically in regards to their racialized, gendered, and otherwise socially located identities. Such thinking has historically left white men operating without detection under intentional social location radars.

Still, what is most befuddling is not that the veil of invisible humanness has been lifted off of white men. What is most confounding for many is the notion that I, a black woman, am so brazenly examining white men and masculinity in public and professional space.

It’s fine. I actually enjoy addressing the anxieties. It is precisely what I am here for.

On initial encounter, people are afraid when I begin to speak about white masculinity.

Black people fear that I may disrupt the overly stacked apple cart that they have managed to balance and push uphill under great duress all with their backs against the cart. Regardless of the inane forces operating against most black people, we are satisfied with momentarily having things figured out. However, because one is pushing the cart uphill backwardly, the log in the middle of the path, which will send everything toppling over, goes unseen. Thus, my speaking threatens the comfort in the scenario by stating: what looks like success is actually a set up by those who stand at the top of the hill watching the scene transpire.

For example, I recently underwent a campaign to have my publishing company release a more affordable version of Abolishing White Masculinity. In the midst of the campaign, a black male colleague of mine texted me stating, “I can buy the book but my name is in another world and attached to many entertainment properties…I have to be careful what I use it for…besides revolutions take mass capital: ex rich white male gays.” I don’t mind his choosing not to participate; everyone has that choice. However, I do find perilous his inability to see the broader picture even in his own analysis. The protection of his “name” is irrelevant if the protection of mass capital is safeguarded–I prefer the term hoarded–by specific factions of society.

In the midst of the campaign, a black male colleague of mine texted me stating, “I can buy the book but my name is in another world and attached to many entertainment properties…I have to be careful what I use it for…besides revolutions take mass capital: ex rich white male gays.” I don’t mind his choosing not to participate; everyone has that choice. However, I do find perilous his inability to see the broader picture even in his own analysis. The protection of his “name” is irrelevant if the protection of mass capital is safeguarded–I prefer the term hoarded–by specific factions of society.

On the other hand, white folks fear that I am angry and only capable of lamenting the hand that life dealt me through oppressive social locations of race, gender, class, and so forth. White men are particularly afraid that they have just entered another conversation where they will be asked to apologize for slavery, while being made liable when they never personally owned any. In this, I recognize that white people are alarmed by their own historical and continuous crises of being and having to wrestle with what threatens their very sense of self-worth.

Again, I am totally here for this and shout: It’s about time that these crises are being dealt with in the public square. We are all responsible for clearing away the obstacles that have kept us from living in our full humanity. One can only heal after understanding that a problem exists and white supremacist ideology (racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, etc.) is very much still a problem. Without studying hegemonic white masculinity specifically as the source for constructing privilege and oppression in contemporary society, then we will always be dealing with the symptoms of oppression instead of disease at its source.

In 2014, it should go without saying that systems of oppression have very little to do with how one feels or self-identifies. Yet, because the systematic structure of hegemonic whiteness (which privileges maleness, heterosexuality, wealth, ability, and more) is grossly misunderstood, we continue to get meaningless statements of “I am not a racist” or “I don’t feel those statements or actions reflect what is in (___________) heart” [You may insert whomever’s name here]. The caricature of white supremacists that rests in most people’s imaginations is a gross and limiting stereotype of racial extremists. Like any stereotype, one can find examples that affirm the perception. But to think of people who explicitly espouse the ideas and ideals of hegemonic whiteness only in the context of the stereotype focuses the attention on a minute population, allowing everyone else a free pass, though we are all functioning in ways that sustain the structure.

In 2014, it should go without saying that systems of oppression have very little to do with how one feels or self-identifies. Yet, because the systematic structure of hegemonic whiteness (which privileges maleness, heterosexuality, wealth, ability, and more) is grossly misunderstood, we continue to get meaningless statements of “I am not a racist” or “I don’t feel those statements or actions reflect what is in (___________) heart” [You may insert whomever’s name here]. The caricature of white supremacists that rests in most people’s imaginations is a gross and limiting stereotype of racial extremists. Like any stereotype, one can find examples that affirm the perception. But to think of people who explicitly espouse the ideas and ideals of hegemonic whiteness only in the context of the stereotype focuses the attention on a minute population, allowing everyone else a free pass, though we are all functioning in ways that sustain the structure.

When we acknowledge that the foundational principles and elements of Western thought and more specifically U.S. culture and society are based upon esteeming whiteness, then we all become card carrying white supremacists. OUCH! That was my response too when I first realized how much I, and everyone around me, have been consciously and unconsciously trained to esteem hegemonic whiteness and to understand the world through white ideas. It is what has led me to know that I am recovering from hegemonic whiteness through my work as a scholar-activist. If I am in need of recovery from the societal and cultural ubiquity of hegemonic whiteness, so too are those who live under the trope and guise of white masculinity.

This is no mammy-fied The Help, looking to destroy the master’s house using the master’s tools statement. It is simple fact.

As a black, Christian womanist walking in the midst of this calling, I have come to embrace the divine need for courageously standing in the gaps for those who may not yet know they are in need of intercession. I do not offer this as an apology for the oppression elicited by hegemonic white masculinity as a constructed trope, nor as a means to make victims out of white men.

Womanism—my feminism, faith and functional practice—is astutely spirited enough to reach for the whole community, all of humanity. Thus, we who walk this particular faith recognize that some of the whole will only come along kicking and screaming. Yet, regardless of the resistance and lack of desire, to leave them behind would be akin to knowingly leaving cancerous cells in the body. It is also counter-productive if the mission is living holistically well. So I don’t engage this work specifically around white masculinity as a means to apologize for those who benefit most from the matrix of domination, but rather to articulate that unless that which is causing the disease is destroyed, we will always remain susceptible to the symptomatic manifestations of its presence.

Not intentionally addressing white men leaves youth like Tal Fortgang perceiving that meritocracy is just as balanced and blind as Lady Justice, sensing that the phrase “check your privilege” marks all his personal accomplishments as “unreal.” He has already demonstrated that, left to his own devices, he will grow to espouse notions like Paul Ryan that minoritized urban bodies simply don’t possess the will and drive to work like good Americans.  He will disregard the implications of protecting hegemonic white masculinity at the heart of every war on this soil from the Revolutionary and Civil Wars to the wars on drugs, poverty, and terrorism. All have been engaged with the ultimate goal of maintaining the privileges afforded to select communities because of the existence of ideologies around hegemonic whiteness while exploiting lives of those who are not white men. (Please note, I am fully aware that wars engaged in by the U.S. on the soil of other nations have done the same).

He will disregard the implications of protecting hegemonic white masculinity at the heart of every war on this soil from the Revolutionary and Civil Wars to the wars on drugs, poverty, and terrorism. All have been engaged with the ultimate goal of maintaining the privileges afforded to select communities because of the existence of ideologies around hegemonic whiteness while exploiting lives of those who are not white men. (Please note, I am fully aware that wars engaged in by the U.S. on the soil of other nations have done the same).

I do not dismiss the fears, anxieties, and obstinate resistance to the current conversations about checking his privilege. I simply want to teach him and others like him, engaging in conversations that may get them to see the forest that surrounds their personalized tree. This is not about the personal, as we collectively like to harp on and can be seen from the recent Donald Sterling melee; it is about the societal and structural. And in this sense, hegemonic white masculinity ultimately screws us all over.

Fortang, a freshman at Princeton University who refuses apologize or feel guilty for being a white man, finds that his accomplishments in life have come and will continue to rest upon his personal achievements. This is why he is at Princeton preparing to major either in history or politics. Ironically, nothing in his now-viral essay discusses what he himself has done, but talks about the traversed narrative of his Holocaust Jewish immigrant grandparents and his self-sacrificing father. Still, I hope he does study History, particularly political and legal history that specializes in federal citizenship legislation. In doing so, he just may learn how interconnected oppression and privilege are. That yes, while Nazi factions were terrorizing Jewish bodies, other allied nations sympathized with their horrors, opening their doors to them for safe harbor and creating earnest pathways to citizenship. However, these same sympathies have never been equally as welcoming to terrorized bodies of Asian nations, indigenous American (North, South, and Central) people, nor African peoples. I hope he learns that it was not until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 that racialized restrictions to citizenship for immigrants were eradicated.

Or maybe he will study a history closer to home and ask, “Why are there are schools know as ‘the ivies’ in the first place?” If all things were equal, what are the historical realities that established a system of “elite” institutions vs. land grants; or simply private versus public spaces of higher education? Maybe he will also ask why Princeton does not continue to minoritize his or anyone else’s Jewishness, but accepts him and his ethnic peers into the fold of whiteness. This question may lead him to grapple with the fact that even international students far exceed Princeton’s African American, Native American, and Latina/o American populations. Why can’t a society that purports its exceptionalism throughout the globe seem to educate enough of its own national “minority” students to be on par with their global colleagues? But I guess this goes against the very premise of Fortang’s argument—it is not the factors of systemic inequality that leave African, Native and Latina/o Americans out of these universities; these communities simply are not exerting enough of their own personal meritorious behaviors to be at a place like Princeton.

This question may lead him to grapple with the fact that even international students far exceed Princeton’s African American, Native American, and Latina/o American populations. Why can’t a society that purports its exceptionalism throughout the globe seem to educate enough of its own national “minority” students to be on par with their global colleagues? But I guess this goes against the very premise of Fortang’s argument—it is not the factors of systemic inequality that leave African, Native and Latina/o Americans out of these universities; these communities simply are not exerting enough of their own personal meritorious behaviors to be at a place like Princeton.

I may be overstating the issues or race in his denial; maybe it’s more about his not apologizing for his gender (though in my own work, I understand the inseparable nature of the two). Still, as a budding student of history and politics willing to grapple with false notions of privilege, I hope he and his peers who are “non-privileged white men” study why in Princeton’s 268 years of history has only one woman, Shirley Tilghman, been meritorious enough to be its president. This may lead him to question why students were initially shocked by her feminism and liberal identities.

Finally, I hope that in the process he would begin to ask why, as a grandson of ethnically marked Jewish grandparents, it is now possible for him to stand in the public square as a white man, having only to disclose Jewishness at his own caprice.

Due to the pervasiveness of white supremacist ideology in US social and institutional conditioning, none of us have fully escaped participating in the use of such practices that inscribe domination onto others. Thus, in light of the boundaries we enact upon one another, through understandings of privilege and oppression, we are all implicated in how hegemonic whiteness thrives. Each one of us is responsible for working to end it. My calling modestly recognizes the grave work that needs to be done toward abolishing dominant narratives of white masculinity.

_____________________________________

Stephany Rose is an assistant professor of women’s and ethnic studies at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs. Her book Abolishing White Masculinity from Mark Twain to Hiphop was released March 2014 by Rowman and Littlefield. For a discount until Jan. 2015 contact @thedrstiletto via Twitter. www.drstephanyrose.com

0 comments