Cross-Cultural Sisterhood: Audre Lorde’s Living Legacy in Germany

By Marion Kraft

In 1986, the first book by Black German women was published.[1] It was inspired by Audre Lorde, who had met some of these women when she was lecturing at the Free University of Berlin. In the preface to the English edition Audre Lorde writes:

To successfully battle the many faces of institutionalized racial oppression, we must share the strengths of each others vision as well as the weaponries born of particular experience. First, we must recognize each other.[2]

“This realization of the commonalities and the differences in the various struggles of people belonging to the African diaspora, of people of color and other oppressed minorities, was closely connected with her belief in the possibility of a truly global feminism and the forging of connectedness.

Already in the 1970s and early 1980, influenced by African liberation movements and the Civil Rights movement in the U.S., Black German individuals had raised their voices against conceptualizations of “race” and racial discrimination in Germany, however, mostly isolated and within the context of other struggles like the students’ or the emerging feminist movement. Thus, for the forging of a collective Black German consciousness of identity, Audre Lorde’s connections with Black Germans were pivotal and marked the beginning of a cross-cultural movement that was seminal for the building of various organizations like the Initiative of Black Germans (ISD), ADEFRA (Afro-German Women) and Homestory Deutschland.

Audre Lorde had a tremendous gift to inspire and empower others. Her powerful poetry led young Black German women to publish their work, in particular the late German-Ghanaian poet May Ayim,[3] after whom a street in Berlin was named in 2010. She encouraged Ika Huegel-Marshall to write her autobiography,[4] wanting to know herself what it was like growing up Black in postwar Germany, and the idea to convene the 5th International Cross-Cultural Black Women’s Studies Summer Institute[5] in Germany in 1991 basically was born out of her belief in action and interaction. Having been the director of this three-week seminar, that took place in Frankfurt/Main, Bielefeld and Berlin with 80 Black women and Women of Color from all over the world and large local audiences still is for me a precious memory. Moreover, this event was another proof for Audre Lorde’s ability to turn the seemingly impossible into reality, to move the Black woman from margin to center – even in Germany. Central speeches and contributions to this convention were later published in a collection of essays.[6] Whereas this important event took place in West-Germany two years after the fall of the Berlin wall, Audre Lorde’s visits to Dresden, in the former GDR was another landmark step to unite Black Germans of African descent with the international Black community.

Twenty years after Audre Lorde’s passing away, her various influences in Germany have been vividly brought to life again in the acclaimed documentary Audre Lorde – The Berlin Years 1984 – 1992[7], and a new volume examines her liaisons with the Black Women’s movement in Germany.[8]

Moreover, Audre Lorde and her works have also left an impact on the white feminist, lesbian and transgender movements in Germany that continues to live on. After a lecture for students of the University of Bielefeld I gave in November 2013, a young white woman said, “I wasn’t aware of all this, I learned a lot, and I envy you for having known Audre Lorde personally.”

Personally, I met Audre Lorde in the summer of 1986 in Berlin. As a Black German feminist, scholar and teacher, I was working on my dissertation on African-American women writers[9], a topic which at that time was marginal in academic literary research as well as in themes and issues of the feminist movement in Germany. I had been reading and studying Audre’s works since my appointment as assistant teacher at Ohio State University in 1975 and was very excited to have the opportunity to interview her. At our first meeting I was almost overwhelmed by her personal warmth, her openness, her analytical mind and the power of her words. To my question about her notion of teaching as a survival technique she responded “I think we teach best those things we need to learn for our own survival. So, as we learn them, we then reach back and teach, and it becomes a joint process. I think that this is what keeps us new, that we do not learn from what goes on in a book. We learn from that interaction that takes place in the spaces between what is in the book and ourselves.”[10] For me, this was not only an insight that reached beyond institutionalized academic structures, but also an empowerment as a Black scholar and teacher in Germany, who was aiming at conveying the histories, struggles, cultures and literature of Afrodescendants to predominantly white student audiences. From this, our first conversation, a deep friendship developed that continued until I last saw her in the fall of 1992 in Berlin.

The poetry readings I organized for Audre Lorde in Germany illustrated her idea of teaching and interaction and her definition of poetry as “the most subversive form of language.” Not only was there the voice of poet, who spoke to people’s hearts and minds, but also the teacher within her, not lecturing but communicating and inspiring her audiences to find solutions for the various forms of oppression in the world and to re-consider notions about themselves and about others. In Germany, it became particularly clear what Audre Lorde meant when she said: “My audience is every single person who can use the work I do. Anybody who can use what I do is who I’m writing for. Now, I write out of who I am, all of the ways in which I describe myself, and so, all those people who share those aspects with me, who are Black, who are warrior women poets, lesbians […] may find themselves closer to what I’m doing, but I write out of who I am for everyone who can use what I’m saying.”[11]

It is in this context, that Audre wanted a selection of her poetry translated into German. I gladly consented when she asked me to meet this challenging task. Together with my colleague Sigrid Markmann and Orlanda publishing house, I decided on a bi-lingual edition that would on the one hand keep the voice of the poet alive and on the other hand facilitate a comprehensive understanding of her insights and her visions.[12] She had mad the selection herself, but did not live to see it in print.

For Audre Lorde, who also defined herself as a cultural traveller, these early transnational encounters and liaisons with Black Germans were inspirational. An experience that shows through in poems like “This Urn contains ash from German concentration camps,” “Berlin is hard on colored Girls” or “East Berlin” and in her essay “The Dream of Europe”, in which she writes: ”For most of my life I did not dream of Europe at all – except as nightmare. […] When I […] [came to Europe] I found people there that now compose my dream of Europe. They are Afro-European and other Black Europeans, those hyphenated people who, in concert with other people of the African Diaspora are increasing forces for international change.”[13]

This vision of international changes Audre Lorde expressed at our very first meeting, when she talked about the necessity of networks and the commonalities of people who define themselves as Black, and their intimate connections rooted in their oppressions by systems of a profit oriented economy. But she also pointed out the differences among the oppressed and the importance of the ability to look at these differences, to use them creatively in order to move toward change, “toward that future we can share.”[14] When I asked her about her hope to reach that goal she said, “I’m really very hopeful. It is a hope, however, grounded in a very realistic estimation of the enormity of the forces aligned against us. […] But I believe we can do it, and not only that, I believe we can do it with joy![15]

Audre Lorde’s Poetry Reading at the Women’s Cultural Center in Bielefeld, Germany

copyright Marion Kraft

Joy, even within the center of various struggles, governed Audre’s visions of life. She enjoyed her poetry readings, her lectures and the communication with her different audiences. But she also enjoyed intimate discussions, celebrations, and to dance. And she enjoyed the beauty of nature. I had the privilege to witness her joy over a particular shell on a shore of the Caribbean Island St. Croix, to which she had invited me, I had the privilege to witness her joy over a special blossom of a plant in my garden, where we prepared one of her poetry readings in Germany, and I had the privilege to witness that her a sense of wonder over the beauty of this world was not contradictory to a sincere commitment to fighting the powers of destruction, to being a warrior, a Black lesbian, warrior poet, to being a mother, and to being able to love. Thus, for me, in the film Audre Lorde – The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992, next to the documentation of Audre’s liaisons with the Black German community, the most important quote is her statement: “I love people, men and women, I have the capacity to love.”

This love of people, this commitment to humanity laid the foundation of her solidarity with the oppressed and her fundamentally important connectedness to Black people in Germany.

________________________________________

Dr. Marion Kraft is a Black scholar and author, born in Germany in 1946. She studied German, English and Philosophy at the universities of Cologne, Columbus, Ohio and Frankfurt/M, graduated in 1976 and received her teacher’s degree in secondary education in 1978 and her doctorate from the University of Osnabrueck in 1994. Her dissertation The African Continuum and African-American Women Writers was published by Peter Lang in 1995. She taught English, Literature and Women’s Studies at the Oberstufenkolleg at the University of Bielefeld and at the University of Osnabrueck. A translator of poems by Audre Lorde and co-editor of an anthology on Black women’s culture and politics, she has also published several essays in German and English on racism, sexism, Afro-German women and on African-American Women’s literature. www.drmarionkraft.com

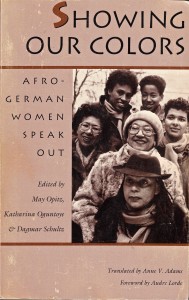

[1] Showing Our Colors – Afro-German Women Speak Out. Edited by May Opitz, Katharina Oguntoye and Dagmar Schultz, translated by Anne V. Adams. The University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, 1992.

[2] Ibid., ix.

[3] May Ayim. Blues in Schwarz Weiss. Berlin: Orlanda, 1995.

[4] Ika Huegel-Marshall. Invisible Woman.

[5] Originally initiated by Andrée Nicola McLaughlin of Medgar Evers College, CUNY.

[6] Marion Kraft & Rukhsana Shamim Ashraf-Kahn. Schwarze Frauen der Welt – Europa und Migration (Black Women of the World, Europe and Migration). Berlin: Orlanda, 1994.

[7] Directed by Dagmar Schultz, 2012.

[8] Peggy Piesche, ed. Audre Lorde und die Schwarze Frauenbewegung in Deutschland. Berlin: Orlanda, 2012.

[9] Marion Kraft. The African Continuum and African-American Women Writers. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1995.

[10] Marion Kraft. „The Creative Use of Difference“, in Conversations with Audre Lorde, edited by Joan Wylie Hall. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004, 152.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Audre Lorde. Die Quelle unserer Macht – Gedichte. Translated by Marion Kraft & Sigrid Markmann. Berlin: Orlanda, 1994.

[13] Audre Lorde. „The Dream of Europe.” Manuscript, translated by Marion Kraft. “Der Traum von Europa”, Dagmar Schultz, ed., Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich – Macht und Sinnlichkeit. Ausgewählte Texte (Berlin: Orlanda, 1991), 216 – 217..

[14] Marion Kraft. „The Creative Use of Difference“, 153.

[15] Ibid.

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire