Coming Home.

By Happy Mwende Kinyili

My name is Mwende and I am a woman. These identities – woman, Kamba, young, sweet – have come easy to me. I didn’t need to meditate upon them so as to find them within the very soul of my being – or something transcendental like that. I just was. Oh, for a (definitive) moment, Christian was another identity that rolled off my lips easily too. I just was.

*******

One Sunday morning, a couple of months into college, I walked into the Black Church. I had been floating around, trying to find a church family. Before leaving for college, my home church family had grounded me. We spent an inordinate amount of time together. We danced, laughed, shared meals, and buried loved ones together. We were family. Many times, my church family gathered at my birth family’s home. Friends would just come on over. The first meal we spread out and shared as a church family was made on my mother’s stove.

I felt adrift without that grounding and went searching for it. Walking up the cobblestones, I heard the music wafting and was drawn in, welcomed to the Black Church. I listened to the sermon that Sunday morning and offered up praise and worship. At the end of the sermon, Pastor Joan made an altar call for people to move on up and find healing. And I broke down, crying for home and comfort of family. My heart shed tears so heavy my body shook to release them. And they were cradled by those gathered in the Black Church. They were held safely by the family gathered in that Black Church.

********

I walked past the black table in the dining hall many times during my college years. I didn’t fully understand the Black table. I found that we could gather around church with some of the people at the table on Sunday mornings but sitting together at that table during meal times felt awkward and stilted. My friend from Botswana could easily move in and out of this crowd – the Africans in America crowd – and sit comfortably with us – the African crowd. I remember asking her to explain what made her comfortable at that table. I really wanted to figure out, to understand the Black table.

I had only one African in America friend in college. All my other Black friends were African. We – my African friends and I – sometimes talked about how difficult it was to find things in common with Africans in America and sometimes found it easier to hang out with white folk. Then, at least we didn’t expect the other person to make intuitive sense, and we did the work necessary to make ourselves understood to the other person.

This separation between the Africans in America crowd and my African crowd was deep. I took many classes in the African studies department, and rarely did I find an African in America in that class. Mostly there were African students and white students. I tried to take a class in the African American studies department, but that didn’t go over too well – I eventually dropped the class because I didn’t feel like I belonged.

*******

Many years later, I made my way back home to The Continent. In mid-October 2011, the Kenyan Defence Forces (KDF) marched into Somalia under the banner of “Operation Linda Nchi”[1]. Operation Linda Nchi’s mission: to combat and bring down Islamist al-Shabaab insurgents who control much of Southern Somalia. The official account relays that the Kenyan government took action and invaded Somalia in a bid to move against al-Shabaab forces following a series of abductions of nationals from western nations. While this action was a violation of the agreement between the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) nations – Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, and Uganda – to not launch a military intervention in Somalia, KDF went into Somalia nonetheless. The other IGAD nations were supportive of this insurgence. At different moments during the insurgence, the President of Somalia, Sharif Ahmed, stated that the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia was fully supportive of KDF’s actions. They too wanted al-Shabaab taken down, or so they stated.

For the duration of the insurgence, the headlines of the major dailies in Kenya rang with patriotic pride of KDF’s successful actions in Somalia. On Mashujaa Day, a national holiday celebrating Kenya’s (s)heroes on October 20th, the President remarked, “We pray for their safety and security as they embark on defending our country, as we decisively deal with this threat to our national security. These men and women are protecting our sovereignty. No one among us is [to be] used to disrupt peace and stability. We should all be vigilant and as true patriots, ensure that we identify the bad elements among us. The hospitality of the Kenyan people must never be abused by some bad elements.”[2]

*******

Most of the time, I have a hard time relating to my sister’s friends: our worldviews are so radically different that our interactions either have me engaged in endless verbal wars or viewed as the evening’s entertainment. However, I didn’t expect to be in such a situation this evening. I always assumed that while we fundamentally laid our beliefs in different sovereignties – Otieno with the Christian God, me with myself – we had seen enough of a similar harshness in the world to agree on the importance of our Black family.

The conversation meandered over to the rising cost of housing in Nairobi. One person chimed in, stating categorically, that this was because of the influx of pirate money from the activities of Somali pirates off the coast of East Africa. Another quickly added that Nairobi’s landlords, however, were very wary of renting houses to Somali people. “Why?” asked another in the room. Well, it turned out, according to our avid story teller, that when Somali people rented houses, very many of them lived together in the house, and when they left, the house was always left in shambles. Of course, not a single person in that room had borne witness to this – but rather, they were repeating a story they heard from a friend of a friend. By the end of the evening, Otieno and I were neck-to-neck, my arguing against his (blatant) xenophobia and ethnic chauvinism, he arguing against my (supposed) naïveté.

And this conversation, taking place in the living room of some bourgeoisie Kenyans, was happening before Operation Linda Nchi was launched.

*******

With the words of our President echoing in our ears, Kenyans went all out to protect themselves from the hands of the rampaging al-Shabaab. The existing xenophobia and ethnic chauvinism in Kenya against the Somali people was heightened. One blogger[3] recounts riding in a matatu in Hurlingham – a Nairobi suburb with a large Somali population – and watching as the conductor pushed an older man who looked Somali out of the matatu, all in a bid to ensure that he, the conductor, played his part in ensuring a safe Kenya. This happened days after a grenade was thrown into a busy bus terminus in Nairobi’s business district, after the launch of Operation Linda Nchi.

Accounts of violence, evictions, and harassment of people who appeared Somali or who identified ethnically as Somali increased with Operation Linda Nchi. Kenyans, who were not of Somali ethnicity or who did not appear Somali, launched an attack against anyone who in their imaginary slightest resembled al-Shabaab a Somali.

*******

Writing these words, the importance of that Sunday morning, a couple of months into my college experience, brought tears to my eyes. My heart hurt from plunging into the belly’s beast, and away from the bosom of familiarity. My heart hurt from dealing with pressures, thus far held carefully away from me by the security of family. My heart hurt from yearning for familiarity and yearning for home. That Sunday morning, I found a moment, a space, and safety to bare my heart and find comfort with family.

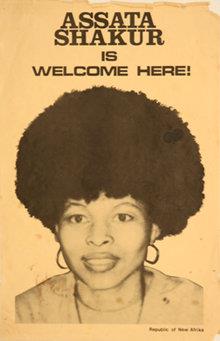

Many years later, I identify as Black. Inextricably, unapologetically, proudly Black. My reading of Assata Shakur’s autobiography was my first direct and deliberate step into understanding Blackness that existed outside my own immediate historical moment. Her words, her bravery, and her sacrifice, ushered me into a bone-deep recognition of family. Take me back to college, and I would definitely sit at the Black table. And not ask for any explanations.

[1] Linda Nchi is Swahili for ‘protect the country’.

[2] Barasa, Lucas. “Kibaki vows to defend Kenya’s territory.” Daily Nation October 20, 2011.

[3] iCon “#KenyaAtWar: The Question of Unity” Diasporadical Tuko Wax Mzeiya, October 28, 2011. Accessed 2 Jul 2013.

______________________________________________________

Happy Mwende Kinyili. My struggle is to identify, name, and confront the oppressions that permeate our lived realities. Thus, my daily toil is to build a world where different injustices are overcome and an alternative community based on revolutionary love, effervescent hope, and emancipatory truth is realised.

Happy Mwende Kinyili. My struggle is to identify, name, and confront the oppressions that permeate our lived realities. Thus, my daily toil is to build a world where different injustices are overcome and an alternative community based on revolutionary love, effervescent hope, and emancipatory truth is realised.

4 Comments