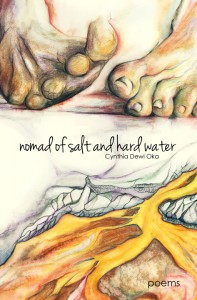

The Place of Our Spines: An Inter/Review of nomad of salt and hard water by Cynthia Dewi Oka

“Poems come to stand in the place of our spines.”

“Poems come to stand in the place of our spines.”

-Cynthia Dewi Oka “notes on Captain Ahab’s workshop/ before the poet is harpooned”

We are at my kitchen table. Sunlight dances through the back screen door. Sendolo, Yashna and Cynthia and I are eating. Cynthia is beaming with pride about the brilliance of her young son Paul. “I mean he says the most poetic things. I don’t know where he gets it.” I look at Cynthia the way you look at a sister: with amusement, annoyance and awe. “Where does he get it?!” I think I am shouting. Maybe I stood up. “What do you mean? Where? His mother is a great poet!”

It is a sister’s job to remind you of very obvious things, like to call when you get home and who you are. (Just in case you get caught up at the kitchen table on a summer afternoon and forget.)

This is an inter/review by a sister of Cynthia. This is written by someone who has known already for years that Cynthia Dewi Oka is a great poet. (Maybe even before Cynthia Dewi Oka could admit it.) This is an essay by someone who has traded poems with Cynthia over email for years and who is thrilled at the arrival of her first book of poems. I am telling you so you don’t expect distance where there is none. But there is distance.

This is written by someone who has never had the luxury of living in the same place as Cynthia. Just now we got into the same time zone and federal unit. This is someone who has watched long-distance as Cynthia has navigated arbitrary national borders and custody limitations and longing. Mostly longing, that we could sit at that kitchen table every time we needed food and a sister around who could remind us of very obvious things.

The ambitious and important project of nomad of salt and hard water is dedicated to those of us who belong to our longing most days and do not have the luxury of home. Seeking to outline the contours of what she called in our most recent conversation a “Nomad Civilization.” Cynthia says:

I realized what I was trying to do was not to make a map but a civilization. That was when the pieces started to come together, the different pillars. So we have the warrior, oracle, daughter, midwife, moon.

Can you imagine? No, you cannot. This is the job of the poet. We nomads, always imagined to be moving between more or less civilized spaces, get to have a civilization. An oracle, a midwife, a warrior, a moon. What could it mean? Here is Cynthia:

The longing for home informs a lot of postcolonial diasporic literature, looking forward and looking back at the same time. In Indonesia, my mother never had citizenship even though she was born there. They sanctioned persecution of Chinese people for generations. When we lived there it was never our country it was never our home. We just didn’t have one.

The book is saying that you don’t have to have a space as home. That’s okay. Home can be moments and you can live with the grief and the sorrow of knowing it, but also with the liberation of not having home. (Mahmoud) Darwish says in the Butterfly’s Burden, I am not going to return to the desert, I am going to turn to the wind. And that means that we can be accountable without feeling ownership.

And it was hard for me a long time, especially after I became I teen mother because I was effectively excluded from my community. It was a very isolating experience but also a very liberating one because I could just reinvent the tools I needed to live. And I did. It is a very engaged form of wandering. It is going to testify to the shit that is going on. Especially as survivors of patriarchal male violence, many of us do not feel that our bodies can be our home. I have to be okay with that too and how to reconcile myself with the world even if I can’t call this my home.

In other words, as Audre Lorde says “poetry is not a luxury” but home is. Cynthia describes the crucial relationship of poetry for those of us who Lorde names in her Litany for Survival as “those of us who love in doorways coming and going.” As Cynthia explains:

“Poetry is not a Luxury,” really hit me on a visceral level. When you are a mom you have to find something inside of you to give to that kid even if nothing is coming in.

I started out writing on napkins and newspaper margins and textbook corners. It was the only way I could keep myself. Between shifts, working all the time, in school being a mom, that margin was mine.

I really didn’t think about doing anything with it. And it wasn’t until I got involved in social justice work and I started feeling like the language was very disciplined, like you had to use these ideological equations and then things were okay to say. And I started feeling that maybe we needed poetry.

In 2009 I went to VONA (Voices of Our Nations Artists Foundation) and worked with Suheir Hammad. She said, “Poetry has literally kept you alive. What are you doing for poetry?” After that I knew I was gonna have to write a book. I knew the only way I was going to skill build was to make a project. To learn to do the thing I didn’t know how to do.

And more recently I worked with Joy Harjo as a mentor and she made it so clear. There is not only your voice there is an ancestral responsibility that is trying to emerge in you and you have to take care of that. And you have to work with more integrity then you ever have before.

And Cynthia’s poetry teaches us to do the things we don’t know how to do, like how to live without home, how to say what must be said in our political movements when there is no jargon to say it, how to work with the integrity our ancestors are demanding. As Cynthia’s narrator explains, “Poems come to stand in the place of our spines.” (37) And this is the skeleton architecture of how Cynthia’s poems help us to stand where we think we cannot.

Cynthia begins each of the five sections of her poems with a legend establishing one of the pillars of the nomad civilization: daughter, warrior, oracle, moon, midwife. The poems that follow could be understood to be the tools, history, context and struggle of the existence of this figure, moments where this figure can cohere. I think of these pillars, the careful pressure points of what is more a mode of being than a place, as fortifications for our particular backbones. Maybe for me it is a scoliosis-driven craving, but in fact the word spine appears in seven difference poems across the collection. From “ode to sambal” to “a litany for home” offering tangibility to almost every section of this embodied work. But for now (until you come over to the house to sit and talk with me about this book all day) I will focus on the spinal clarifications in “ocean’s ingot,” the section organized around the nomad legend of the warrior. (See: ongoing shout out to the warrior poet Audre Lorde!)

In “(unsubmitted) prospectus of a native informant,” a poem that takes on academic forms with incisive interventionary power, the narrator mentions the spine early on. In the first section of the poem, entitled “subject/object construction” the narrator explains it is “time to realign bone in the text of my spine,” emphasizing the bodily work it takes to enter spaces of dominant knowledge production and also revaluing the spine as the “only barricade” between the speaker and the pressures of life, from rent, to loans, to sleep deprivation (26). Later in the same poem, in the context of a series of definitions set out as the “ontological premise,” the spine cannot remain intact. (Re)definining the proposition of the term palimpsest as “my back broken of insolence & ironed/for mercury to engrave any alphabet…” the speaker points to the way the academic context is in direct opposition to the resilience of that back bone that has allowed “the native informant” to survive economic, racist and gendered oppression (27). Her back must be broken and refitted to form more raw material for a dominant narrative. And indeed as she explains later, the nomad knows what it means to “beg for time and calcium,” the alternate “canon” she proposes is composed of bone that “derives no prestige from ivory,” set to outlast and potentially blast academic vogue with a “guerilla heart.” (29)

And in fact, publishing this nuanced book of poems with Dinah, a new feminist collective press based in Los Angeles, Cynthia and her publishers are helping to model how the work of creating poems can be rigorous without being back-breaking in the physical and spiritual senses. As Cynthia explains:

Dinah’s vision is a process of really challenging this idea that publishing and writing are this sort of privileged act in an elitist world. We can do it in a way that is more humanizing to us. So the process is slower because everything is decided by consensus. There is a lot of respect. All of the editors work for free and they invite you to be an editor and you can choose what you want to do to build your own skills including helping to choose the next round of manuscripts. On a practical level that is really helpful. They are committed to amplifying underrepresented voices and stories and they are very committed to quality as well. I really felt that when I got their feedback. I was very impressed with how thorough they were. There is solid politics and commitment to really good craft. And camaraderie.

They gave me so much autonomy, they were very straightforward, they critiqued the manuscript. There was an agreement to be compassionate with each other but also real. I feel that I had not experienced that in other collectives where people would not say what they needed to say to avoid conflict. With Dinah they took their time with the manuscript and when they came back they had serious critique.

With writers of color our first work is always a testament that we exist. Writers of privilege don’t have to make that explanation. It was very important for my first book for me to have autonomy. And no there isn’t a ton of money and sometimes it takes a long time but the human side is that I don’t feel alienated from the thing I just gave birth to. Very important.

Long story short? I am going to be a sister to you and tell you something very obvious. You should read nomad of salt and hard water. You should keep paying attention to Dinah Press. It is good for your bones, it is better than the chiropractor for those of us who are engaged wanderers hoping that the poetry that saves our live can come into the world in an ethical way that allows us to stand in the presence of our ancestors, bad backs and broken hearts notwithstanding.

0 comments