E(race)sure, Queerness, and Civil Rights in the South: The Undocubus and the Legacy of Bayard Rustin

By Brittany D. Chávez

As a queer woman of color artist-scholar-activist living in the U.S. South, I am deeply invested in historical legacies of queer people, people of color, and undocumented immigrants in their/our struggles for civil rights. I was incredibly inspired by the Undocubus riders and their “No Papers, No Fear Ride for Justice” that traversed the South in the summer of 2012, ostensibly following the legacy of the Freedom Rides.

The bus, Priscilla, is covered in butterflies representing and anthropomorphizing the desire for freedom of migration as open as mariposas. The riders traveled through many states that have passed hateful legislation against immigrants in the last few years, including Arizona, Colorado, Florida, New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, arriving in Charlotte, North Carolina, at the Democratic National Convention that took place between September 4-6, 2012, to demand that deportations stop and that immigration reform be adequately addressed. For their action of civil disobedience at the DNC, a group of riders was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and later released. The rides demonstrated how Latinas/os and other undocumented immigrants are putting their bodies on the line to perform their way into a historically binaristic black/white civil rights landscape in the U.S. South—the implications of which are immense and the discourse yet still too little. Why have we, (activists, scholars, feminists, citizens, and all those who dare to call ourselves “allies”), not made a bigger deal about this phenomenal event?

The bus, Priscilla, is covered in butterflies representing and anthropomorphizing the desire for freedom of migration as open as mariposas. The riders traveled through many states that have passed hateful legislation against immigrants in the last few years, including Arizona, Colorado, Florida, New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, arriving in Charlotte, North Carolina, at the Democratic National Convention that took place between September 4-6, 2012, to demand that deportations stop and that immigration reform be adequately addressed. For their action of civil disobedience at the DNC, a group of riders was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and later released. The rides demonstrated how Latinas/os and other undocumented immigrants are putting their bodies on the line to perform their way into a historically binaristic black/white civil rights landscape in the U.S. South—the implications of which are immense and the discourse yet still too little. Why have we, (activists, scholars, feminists, citizens, and all those who dare to call ourselves “allies”), not made a bigger deal about this phenomenal event?

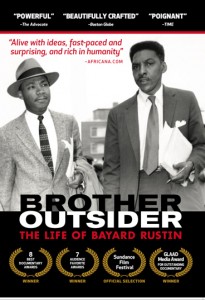

As I set out to write about the legacy that the Undocubus riders followed in what I call a performance of civil rights, my research initially took me to the Freedom Rides of the 1960s—the familiar story that I had always been taught. But then I viewed the film “Brother Outsider” and discovered the history of Bayard Rustin—a history I had not been taught. As a half-black woman educated in California’s public schools in various Gifted and Talented Education programs, I was perplexed and appalled as to why I had never heard of Bayard Rustin until now—as a doctoral student in the South. I began to ask questions about queerness and erasure and to dig deeper. Why was I just now learning that it was Bayard Rustin, an outwardly gay black man and activist, who organized the first Freedom Rides on April 4, 1947 as part of the “Journey of Reconciliation”? And that it was Rustin who had organized the March on Washington (August 28, 1963)?

I knew I could not be the only person with this gap in historical education. So I ask: Is there a gap in our collective historical memory? Do we want to forget that it was an outwardly queer black man who led the first true Freedom Rides for integration across the United States South? Had he not been queer—and unapologetically so—would this erasure have happened?

I knew I could not be the only person with this gap in historical education. So I ask: Is there a gap in our collective historical memory? Do we want to forget that it was an outwardly queer black man who led the first true Freedom Rides for integration across the United States South? Had he not been queer—and unapologetically so—would this erasure have happened?

The Undocubus and other civil rights mobilizations around the undocumented movement in the United States in the last several years include essential queer lenses, as many undocumented people in this country are also queer. By queer lenses, I mean the ways in which the undocumented debate and its activists see themselves in conversation with struggles for queer liberation. (For more information on people writing on queer migration, see the Queer Migration Research Network.) There were also a number of queer and undocumented people on the Undocubus. These intersections have major implications for the ways that undocumented immigrants are performing themselves into the civil rights landscape in the U.S. South and elsewhere. Among which are the ways undocumented activists and allies speak of “queering the undocumented debate” and “queering the border” to add analytical complexity and nuance, and to ask what queer and undocumented immigrant rights groups have to learn from one another and what the significance of this intersection is. As “Latina/o” is not a race, per se, and the Latina/o undocumented migrant struggle cannot be conflated with black struggle in the same way that being queer cannot be equated to any identity of Otherness like blackness, the Undocubus troubles these all-too-frequent subsumptions-erasures.

Democracy Now covered the Undocubus rides and I also followed a few friends on Facebook who participated. Yet in the public sphere, it is almost as if the rides never happened. Activist groups throughout the country, including one I participate in (SONG—Southerners on New Ground), are taking up the Undocubus legacy and trying to carry the movement forward. But in the mainstream public sphere, we have not seen a continued dialogue, acknowledgment of what happened, or admissions for needed and pressing change. Why? Along the same vein that Bayard Rustin has been erased from the history books as the initiator of the “Journey of Reconciliation” in 1947, I wonder if the Undocubus rides get erased, in large part, because of their queer strategies of resistance and struggle? I have to wonder when we will stop erasing these very important histories and luchas and whether queer fear is the culprit.

As a self-identified black feminist, I feel an obligation to participate in historical re-making—to participate in and insist on my response-ability in education and activism. In movements for coalition and the struggle for undocumented Latinas/os and other undocumented groups to perform themselves into civil rights history in the South, we cannot afford to e(race) the footprints our black brothers and sisters left for us and we cannot erase the queer histories and bodies that fortify struggles for social justice. E(race)sure should not be an option and we must insist that it not continue to happen.

Jerald Podair recounts the history of the Journey of Reconciliation:

As planned by Rustin and CORE [Congress on Racial Equality] executive secretary George Houser, it would send interracial pairs on buses through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky to challenge segregation and enforce the Morgan decision. Rustin and Houser recruited a team of fourteen men, divided equally by race, to ride south with them. They all came from the radical wings of the pacifist and civil rights movements. Rustin tried to interest the mainstream press in the Journey, but only two black newspapers provided coverage, an indication of CORE’s low profile in national media at the time (Podair 27-28).

Not only were the mainstream presses not interested in CORE, they were also not interested in an outwardly gay black man being the face of any civil rights movement. During the journey, Rustin and six other riders were arrested after boarding a bus in Durham, North Carolina. Another group of riders was also arrested with Rustin in Chapel Hill, near the University of North Carolina. When asking these historical questions, I cannot help but emphasize the feelings of historical memory that resonate in my very bones and move me to speak and to write about hidden histories.

Not only were the mainstream presses not interested in CORE, they were also not interested in an outwardly gay black man being the face of any civil rights movement. During the journey, Rustin and six other riders were arrested after boarding a bus in Durham, North Carolina. Another group of riders was also arrested with Rustin in Chapel Hill, near the University of North Carolina. When asking these historical questions, I cannot help but emphasize the feelings of historical memory that resonate in my very bones and move me to speak and to write about hidden histories.

On January 21, 1953, after speaking at an event in Pasadena, California, Rustin, in typical form, went looking for male company afterward. He was usually able to avoid authorities but on this night, he was caught having sex in a car with two white men and was arrested (Podair 33). Rustin was kicked out of his home base, Fellowship of Reconciliation, because its leader, Muste, believed homosexuality to be a biblical sin. Arguably, one of the most threatening things about gayness to all forms of normativity is the sex, especially public sex—éso no se hace. Queer sex deployed by a black body to white bodies meant, for Rustin and the rest of us, the attempted erasure of a very important moment in black civil rights history.

Rustin is remembered by many for “morals charges” as a gay man having sex than for his important role in civil rights struggles in the United States. We must stop shaming queerness—all of queerness. Though perhaps a radical gesture, can we embrace all of Rustin, even his sex, and write him back into the history of civil rights enacted by the Undocubus riders? Can we, through this, say that the legacy the Undocubus riders were following is that of the “Journey of Reconciliation”?

The Undocubus was a historic event that should have been met with response and mobilizations of epic proportions, but its queerness has knocked it off our collective radar. We must continue to ask why and how we have allowed this to happen in the same way that we have to ask how many people know of or are taught the history of Bayard Rustin? Black and Latino civil rights have much to learn from one another, and we belong in this struggle together. ¡Ya basta! We must stand up, shout out, and remember Rustin, stand on the front lines with the riders in their continued struggle for migrant justice, and ask how we can fight together and alongside one another: queer, colored, and fierce. This should be the minimum requirement for true allyship.

The Undocubus was a historic event that should have been met with response and mobilizations of epic proportions, but its queerness has knocked it off our collective radar. We must continue to ask why and how we have allowed this to happen in the same way that we have to ask how many people know of or are taught the history of Bayard Rustin? Black and Latino civil rights have much to learn from one another, and we belong in this struggle together. ¡Ya basta! We must stand up, shout out, and remember Rustin, stand on the front lines with the riders in their continued struggle for migrant justice, and ask how we can fight together and alongside one another: queer, colored, and fierce. This should be the minimum requirement for true allyship.

¡Adelante!

________________________________________________

Brittany D. Chávez is a performance artist, activist, and PhD student in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her scholarship, activism, and performance work center on queer Latina/o migration, oral history, and radical body performance. Brittany is deeply invested in the ways that queer and colored migrant bodies transgress and resist dominant politics and in placing her own body into those spaces. Her written scholarship also appears in Text and Performance Quarterly.

Brittany D. Chávez is a performance artist, activist, and PhD student in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her scholarship, activism, and performance work center on queer Latina/o migration, oral history, and radical body performance. Brittany is deeply invested in the ways that queer and colored migrant bodies transgress and resist dominant politics and in placing her own body into those spaces. Her written scholarship also appears in Text and Performance Quarterly.

32 Comments