Lose like a Man: Who is Really Losing in the new Weight Watchers Campaign?

By David J. Leonard

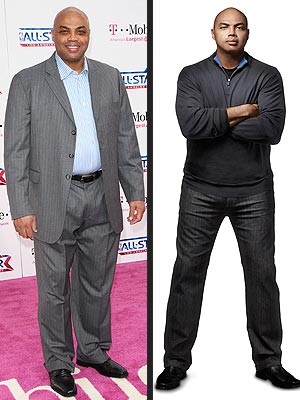

It seems that Charles Barkley is everywhere and that isn’t just because there are basketball games on each and every day due to the compressed post-lockout schedule. Whether appearing on Saturday Night live or Sunday Night Football, Barkley has emerged as a highly recognized figure since his retirement from professional basketball. Yet, his ascendance has reached new heights recently with the launch of his “Lose like a man” campaign with Weight Watchers.

Barkley’s struggle with his weight since his retirement has been well documented, often the butt of jokes on his TNT’s NBA Tonight. It would seem that this laughter and joking stops with his new Weight Watchers commercial. In front of an all-black screen and wearing all black clothes, Barkley announces:

I am still not a role model. But maybe I can change that. Maybe if I tell you that I am losing weight and getting healthy you will see that you can to. Maybe if I said I was stopping making excuses and started making progress, you’d do the same. And maybe if I told you I was doing it with Weight Watchers, you’d join me. Lose like a man.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dCacR-_0ng

Referencing Barkley’s “I am not a role model” NIKE commercial, the commercial establishes a firm binary between his past hypermasculine ways and his new more refined and skinny self.

The commercial presents Barkley as a role model because he is able to lose weight, to show his vulnerability, all while maintaining a clear articulation of manhood. Weight Watchers, in fact, allows for this successful balance. In an online spot, Barkley further articulates the gendered approach to weight loss:

Every guy thinks they can install the dishwasher themselves until they blow up the kitchen. And every guy thinks they can lose weight on their own. Look around guys, it ain’t working. Weight watchers has a plan for men; it has helped me lose 23 pounds already and gives me the tools to keep losing. I tried doing it myself; it didn’t go to well.

The efforts to capitalize on the ways in which weight-loss and body image have been feminized within the national discourse are fully evident here. In defining weight loss in gendered terms Weight Watchers reifies the boundaries of gender, ultimately concluding that men can remain men even if they are losing weight. The commercial, therefore, imagines weight-loss as a feminine domain, one that men can enter as long as there is a parallel masculine space. Lisa Guerrero, an associate professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender, and Race Studies at Washington State University, identifies the commercial as part of a larger process of gendering behaviors, objects, and processes. Like other examples of gendering of food – “man food” v.“chick food” – the Barkley spots are “yet another example of what Butler would call ‘girling’ or ‘boying’ discourse, which directs ‘appropriate’ gendered behaviors. Butler made clear the power and hegemony of gendering:

Consider the medical interpellation which (the recent emergence of the sonogram notwithstanding) shifts an infant from an ‘it’ to a ‘she’ or a ‘he’, and in that naming, the girl is ‘girled,’ brought into the domain of language and kinship through the interpellation of gender. But that ‘girling’ of the girl does not end there; on the contrary, that founding interpellation is reiterated by various authorities and throughout various intervals of time to reinforce or contest this naturalized effect. The naming is at once the setting of a boundary, and also the repeated inculcation of a norm (Butler 1993, p 7-8).

His emergence as the newest spokesperson, especially in relationship to other African American women for weight loss companies, leaves one wondering if these companies are attempting to reach African American consumers. In my previous writing about national obesity rates, I explored the ways in which race and class are in operation:

The numbers are telling. 34% of adults are obese with another 34% in the overweight category. For kids, things are equally troubling with 18% of kids ages 12-19 and 20% of those ages 6-11 defined as overweight.

This issue is particularly acute within the black and Latino communities. Nationally, 38.2 and 35.9 percent of African American and Latino youth, ages 2-19, are obese and overweight, compared to 29.3 percent of whites within this same age group. In nine states, adult obesity for African Americans exceeds 40 percent with that number between 35-39.99% for 34 states. “Strikingly, the link between race, poverty and obesity is most acute in the South, our nation’s most impoverished region” writes Angela Glover Blackwell. “In Mississippi, which has an African American population of more than 37 percent and is the poorest state in the country, the obesity rate is the highest of any state, as is the proportion of obese children ages 10-17.” Worse yet, despite attention and a national discourse, the obesity issue doesn’t seem to be getting better, especially when we look within (poor) communities of color. Between 1986 and 1998, childhood obesity rates within the African American and Latino communities increased by almost 120 percent, whereas whites only saw an increase of 50 percent over this same period. According to the NAACP, “these rates have roughly doubled since 1980.” It has been estimated that roughly 60 percent of Native Americans living in urban communities are overweight or obese.

As with much of the national discourse surrounding obesity and weight loss, the Barkley commercial, and the entire weight-loss industry, work from a paradigm of choice. Erasing segregation, racism, food deserts, and class inequality, the commercial seems to target African American men, but obscures the profound ways that Weight Watchers is more readily available to white suburban women. According to a story on Weight Watchers in Baltimore, “the typical Weight Watchers client is an upper-middle class women living in the suburbs.”

Barkley’s spot continues a recent trend of African American celebrities hocking products for the weight-loss industry. Jennifer Hudson, Mariah Carey, Janet Jackson, and Queen Latifah have all appeared as spokeswomen for Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig, and Nutrisystem. While perpetuating the gendered realities of both the weight-loss industry and the importance placed on beauty/slender body types, the emergence of several black women in these commercials requires some reflection. At one level, we can see the ways in which black celebrities and the commodification of blackness within the realm of popular culture has found its way into the weight-loss industry. It is merely an extension of the commercialization of blackness. At another level, we can see the ways in which these companies are using famous black women as part of its efforts to increase the market share within the African American community. In “Why Black Women Are The New Face Of The Weight Loss Industry,” the NewsOne Staff describes, “these weight loss commercials will help give black women the control needed to create their own narratives of African-American imagery and femininity for public discourse.” Allison Samuels, in “Weight Loss Ads’ New Black Stars: Janet Jackson Joins Jennifer Hudson,” similarly links these commercials to an effort to reach out to African American women:

What Jackson, Hudson, and Carey all seem to have are extra pounds that require much more than exercise to lose. African-Americans, and African-American women in particular, have struggled with the issue of weight and weight loss for years, often questioning whether European standards of beauty and size apply to other cultures and races.

Samuels points to a troubling aspect of the ways in which black celebrities are being used by the weight-loss industry. As blackness has been historically signified as pathological, undesirable, and dysfunctional through representations and references to body, weight, and obesity, their transformations under the guise of “white” diet plans operates through a civilizing discourse. In documenting the historic dialectics between race, gender and commodification, Anne McClintock highlights the links between modernity, civilization and hygiene, and the “uncertain boundaries of class, gender, and race identity” (1995, p. 211). Arguing that access to and concern about cleanliness and hygiene, amplified through commodity culture, represented a clear break between the civilized and the uncivilized, the desired and the undesirable, the citizen and the Othered subject. “Soap offered the promise of spiritual salvation and regeneration through commodity consumption, a regime of domestic hygiene that could restore the threatened potency of the imperial body politic and the race” (1995, p. 211). Beauty, appropriate bodies, fitness, and skinniness function in similar ways with Barkley and Hudson entering the territory of the desired and celebrated Other. Weight Watchers transforms Hudson, and more specifically Barkley, from “fat” and “undesirable”–from non-role models to role models worthy of national adoration. Acceptance comes not only from adaptation to “European standards of beauty and size,” but from their exposure to the systems and skills purportedly practiced by wealthy white suburbanites. Discussing the Barkley commercial, Darnell Moore, a visiting scholar at the center for the study of gender and sexuality at New York University, noted how it “says everything about the ways we understand black masculinities as hyper masculine.” His fatness, just as his toughness and outspokenness, required “policing,” demonstrating why he and Jennifer Hudson are powerful commodities for the weight loss industry.

Just as Barkley has been “transformed from rebel to an elder” (Boyd and Shropshire 2010, p. 10) through denunciation of “ballers of the new school,” his maturation, role on TNT, turn as weight-loss spokesman, and weight loss, mark the culmination of this transformation–from a hypermasculine black baller – “the round mound of rebound” – to a refined, desirable and civilized role model. If only we could have a commercial focused less on transforming bodies and more on transforming communities. Now that is a campaign I can support.

___________________________________

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan, layupline, and Urban Cusp. He is a past contributor to Slam, Loop21, The Nation and The Starting Five. He blogs @No Tsuris . Follow him on Twitter @DR_DJL.

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan, layupline, and Urban Cusp. He is a past contributor to Slam, Loop21, The Nation and The Starting Five. He blogs @No Tsuris . Follow him on Twitter @DR_DJL.

0 comments